Short story: The boat in the shed, by Kyle Mewburn

Posted: Thursday May 09, 2024

“How easy it would be to slip a kayak into the river at the back of Len’s section and glide silently past the row of sleeping houses…”

Short story: The boat in the shed, by Kyle Mewburn (newsroom.co.nz)

Everyone thinks he’s dead. Every day they expect his body to be washed up along the coast. Most likely up Karitane way, the way the tide’s running.

But nobody’ll be too surprised if his body’s never found. Even in death he wouldn’t have wished for such attention. He would have gone to great pains to end his life as discretely as he’d lived it, and as tidily as he’d ended Trudy’s. (His only indiscretion, as far as we know.) It must be frustrating for the police, I imagine, to be faced with a community so implacably convinced of his death. Last week they even turned up at the Film Society, turning a blind eye to the lingering pall of sweet-scented smoke in the interest of furthering their enquiries. What kind of man, they wondered, could plan such a meticulous murder, yet make no effort to conceal his guilt (not even to wipe his prints from the hammer), then quietly vanish without a trace.

So we told them everything there was to tell about Len. How he’d been coming for twelve years, every Tuesday without fail — including the night of the murder. As usual, he’d bought a single jug of home-brew and had sat in the same chair in the same corner, quietly sipping his beer. As soon as the credits began to roll, he’d downed the last of his beer, then walked out into the night. There was nothing unusual about his coming alone. Trudy never came with him. And there was nothing in the movie to inspire his later actions.

“Nothing else?” they asked, implications curling their eyebrows.

“He had a small aura,” someone suggested helpfully.

They closed their notebooks with a sigh.

“And the reason you’re all so damn sure he’s dead is because his boat’s still in his shed?”

By now, all that’s left to us is a shrug. I guess it’s only natural they don’t understand. They haven’t been here these last seven years to see his boat grow out of nothing more than wishful thinking, have they? That boat was his single passion — or at least the only one he might give occasional voice to . . . if Trudy ever let him get a word in edge-wise.

“What good’s a bloody boat when we’re living in a dump?” Trudy would scoff each time the subject was broached. “It’s not like he’s ever going to use the bloody thing.”

Trudy was never what you might call a genteel woman. I guess that’s even what attracted him to her . . . once upon a time. Nobody ever questioned the size of her aura.

Join our free readingroom newsletter, for the best literary coverage in NZ.

“It’s an Aleutian sea kayak,” Len would mumble as his face reddened beneath the spotlight glare of sympathetic eyes.

“Bugger fixing the leaks in the roof or finishing the bathroom!” Trudy would continue with a gaoler’s disdain. “What we really need is a bloody boat!”

There was a lot of interest in Len’s boat in the beginning. People were always popping by to check on progress as Len translated the plan’s hieroglyph swirls into forms, and the boat began to take shape. It was like being at an archaeological dig, watching the bones of some ancient aquatic creature being painstakingly revealed. About as exciting, too.

Interest petered out as soon as progress stalled. In its place came a gentle, grinning mockery. “Plannin’ on paddling to South America, are ya Len?” A wink never quite softening the blow.

Len took all the ribbing with a good-natured smile. He wasn’t in a hurry. And the boat gave him an excuse to escape to his shed. Not that Trudy let him escape too often. She was always giving him jobs to do. Everything, it seemed, was more important than Len’s boat.

But he never once complained. He’d finish whatever chore Trudy gave him, and only when she’d run out of ideas, or the energy to pursue him further, he’d slip away to the shed. Sometimes, during one of Trudy’s infamous pot-lucks I’d suddenly notice Len wasn’t there. When I went outside for a pee, I’d see the light burning in the shed. I seldom had the heart to interrupt him.

For three years his boat was little more than a skeleton as he spent untold hundreds of hours cutting a beam of knot-free cedar into centimetre-wide strips. Untold hours more feeding each one through a thicknessing machine. Turning a single length into so many hundred chopsticks. Then he repeated the process with the poplar he’d had to get milled specially by a bloke near Lismore. Nobody milled poplar commercially anymore.

“No wonder,” I snorted, remembering long sweaty afternoons topping a row of poplars, then chain-sawing them into lengths. I thought I’d solved my firewood problems for that year. But it went up in weeks like so many rolled up newspapers.

“It’s a very under-rated timber,” Len disagreed in that earnest way of his. Without another word he slid a three metre length from the pile, and began waving it about, sending ECG oscillations whipping along its length. “See, it’s very light, and very flexible.”

It was little wonder, really, that local interest waned so quickly. I would have lost interest too, if Len hadn’t taken time to explain its appeal.

“It’s an eighteen foot Aleutian sea kayak with a beam just under three feet,” he whispered with a weighty solemnity, the plans unfurled before him like a treasure map. “It only weighs forty-eight pounds but can carry more than three hundred. It’s got a high volume bow and radically cambered foredecks, and the stern’s shape means train-like tracking and minimal weathercocking . . .” As he paused for breath, he gave a self-effacing smile. “Basically it means it’ll keep going in a straight line no matter how rough the seas or how bad the weather.”

The boat’s beauty was an elusive thing. It had as much to do with personality as an accumulation of curves and sleek lines. If you didn’t take the time, you’d miss it. Like watching an ostensibly plain woman unfold her beauty before you like a peacock. Suddenly you can imagine falling in love.

Len certainly loved his boat. Sometimes he must have just stood there watching it for hours, enamoured by a vision none of us shared.

As the years passed, the boat slowly took shape. Until all that was left was the fibreglassing. I suggested the moment warranted some kind of celebration. But Len shook his head at my naïve presumptions. The fibreglassing could, it turned out, also take years. It needed just the right temperature held constant for four days. The first coat was critical. If the temperature altered more than a few degrees, the hull would be irretrievably rippled. You only got one go to get it right.

“It’s not often we get four perfect days in a row,” I said.

Len just shrugged. Always patient with things he had no control over.

So he waited. Waited for four days of stable, warm weather.

I remember vividly the day I dropped by and found him caressing the upturned hull, looking happier than I’d ever seen him. He looked almost guilty when I coughed. At the time I put it down to embarrassment.

“So it went well, did it?” I asked as my hand slid along a hull as smooth and shiny as a mirror.

Len dragged a tarpaulin over the boat. “To keep the dust off,” he said, by way of explanation. “Coffee?”

I didn’t think anything of it at the time. Len was always a little secretive about his boat. I imagined he didn’t want anyone to know it was virtually finished. Especially not Trudy. But now Trudy’s dead and Len’s missing. And his boat’s still in the shed. Finished at last. With the paddle nestled carefully inside the cockpit.

The police are starting to come round to the notion he might be dead after all. The car’s still where he left it and the bank account hasn’t been touched. They’re confident they’ll find him one day – dead or alive.

They asked me to come around to Len’s house the other day to see if there was anything missing. Turns out I was his most frequent visitor. So I told them everything I knew about Len and Trudy and Len’s boat.

At least I thought I did. Until the detectives departed and I was left standing in the shed with the constable who’d stayed behind to lock up behind us.

“Nice boat,” the constable said.

“It’s an Aleutian sea kayak,” I said. “Eighteen foot long with a high volume bow and radically cambered foredecks.” Surprising how much information I’d soaked up over the years.

“The guy must’ve cracked, I reckon,” the constable said. I think he might have said something else, but I can’t be sure anymore, because as I withdrew the paddle, memories of my final visit came flooding back. It had been only a week or so before the murder, but for some reason I hadn’t thought to tell the police about it. Guess it must have slipped my mind.

I’d popped by to return a tool I’d borrowed. Len obviously hadn’t heard my call, because when I pushed open the door his head jerked up like a deer hearing a hunter’s crackling footfall, already realising it was too late. He’d been lovingly polishing the paddle with long, fluid strokes. That was all. There was no reason his eyes should be prised so wide by fear and guilt. No reason as far as I knew.

“Strange paddle,” I said.

He looked at it, then at me. Finally he nodded.

“It’s an Inuit paddle,” he explained. “The blades are flat, not curved, and they’re set perpendicular to the shaft. You lose a little power, but you don’t have to twist your wrists between strokes. So you can paddle a long way without getting tired.”

I could tell he was still feeling uncomfortable, so I’d left.

“Nice paddle,” the constable commented, interrupting my reverie.

“He made it all by hand,” I explained distractedly. “Hollowed out the shaft, laminated the timber together, carved it then polished it.”

“Fancy piece of work,” the constable said.

“Yes,” I agreed, sliding my hand gingerly along the elegant curve of the blade before returning it to its gleaming scabbard, “very fancy.”

Frowning, I climbed up onto the stool in the corner, grabbed the loop embedded in the ceiling, and pulled. I can’t say I was too surprised when what I’d always imagined as a trapdoor noiselessly unfolded into a doorway and a staircase slipped down. I’d never been in the roofspace before. It was bigger than I’d imagined. Big enough to store anything.

“We’ve already looked up there,” the constable called up after me. “There’s nothing but an old set of trestles and a tarpaulin.”

He was right, of course. There wasn’t anything up there. Not anymore.

“How long did you say he’d been building his boat?” the constable asked as I rejoined him. “Seven years,” I said.

“Long time to build a boat,” the constable whistled.

“That’s what I used to think,” I said, as I caressed the hull with an affectionate hand. It was a beautiful boat, despite the ripples creasing its skin. It was rare having a run of four days of stable weather, I thought. Eight days had obviously been impossible.

“What a waste, eh?” the constable said, shaking his head.

Depends on how you look at it, I thought. But I didn’t say so.

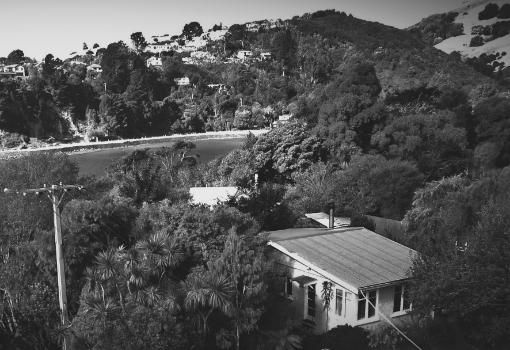

As I headed home, I thought how easy it would be to slip a kayak into the river at the back of Len’s section and glide silently past the row of sleeping houses out into the estuary. The boat’s high volume bow would cruise through the breakers. And suddenly there’d be nothing but open sea between you and Chile.

Kyle Mewburn is the author of the new best-selling novel set in Otago in 1928, Sewing Moonlight (Bateman, $38), available in bookstores nationwide.