Xmas: the best poetry books of 2023

Posted: Monday Dec 18, 2023

Erena Shingade selects the 10 best poetry collections of 2023

Read Original Article: Xmas: the best poetry books of 2023 (newsroom.co.nz)

2023 has been a solid year for poetry in Aotearoa, with a meaty chunk of single author collections. There was also an addition to the AUP New Poets series, two excellent anthologies that highlight oral poetries (Rapture: An Anthology of Performance Poetry from Aotearoa New Zealand, edited by Carrie Rudzinski and Grace Iwashita-Taylor and Remember Me: Poetry to Learn by Heart edited by Anne Kennedy), and the much-anticipatedfirst book from the team behind the collaborative journal Bad Apple. Spoiled Fruit: Queer Poetry from Aotearoa edited by Damien Levi and Amber Esau promises to “bring forth themes of growth, evolution, change and transition through the rot”.

Picking a top 10 always entails idiosyncratic selection so before we get into it, some context and honourable mentions. For this round up, I read 24 single-author collections, mostly from major publishers with a few small presses in the mix. Just under half of them were debuts, some spanning the well-worn territory of childhood nostalgia and bad TV shows from the early noughties, while others took a sober, more light-footed approach. Jake Arthur’s A Lack of Good Sons was particularly charming for its combination of assurance and vulnerability, and allusions to early modern poetries. This beautiful fragment from the poem ‘Confessional’ will be with me for a long time:

On a pew I rest my head and look up,

the colonnade a forest to a stone ceiling;

in me, too, an awful lot of rock.

Most of this year’s books were collections of individual poems, but a couple were structured as a singleproject or accumulating narrative. Ruby Solly’s The Artist could be described as a verse novel (more below), and Rushi Vyas’ When I Reach for Your Pulse uses recurring mantras and funeral rites to explore a father’s death and the struggles of one South Asian American family. Two other collections with a major point of focus include archival research: Deep Colour by Diana Bridge builds on her studies of classical Chinese by including translations as well as ekphrasis of mediaeval artworks, and Michele Leggott’s Face to the Sky brings historical context to Taranaki from a Pākehā point of view through old newspaper reports and early settlers’ letters.

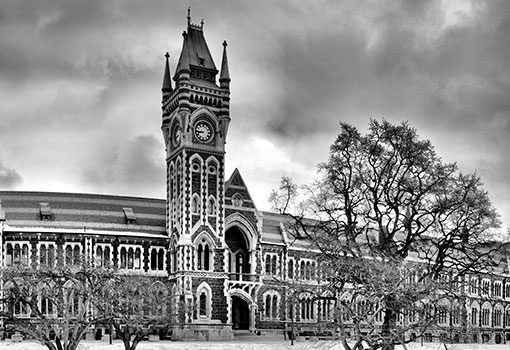

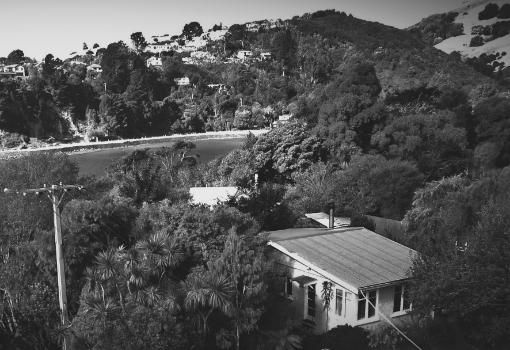

The number one most popular theme in the 24 books of poetry was – perhaps unsurprisingly – the natural world. Ecological surroundings, whether the speaker’s own garden or the tangly weeds of the Otago Peninsula were given reverential attention by Stephanie de Montalk (As the trees have grown), Diana Bridge (Deep Colour), Megan Kitching (At the Point of Seeing), David Eggleton (Respirator), Robyn Maree Pickens (Tung), James Norcliffe (Letter to ‘Oumuamua) and Claire Orchard (Liveability). A further sub-category of ‘landscape poetry’ seems to express the belief that spiritual salvation can be found in the natural world, and that complicated human affairs are best kept at arm’s length (see the art-poetry collaboration In the Temple, by Catherine Bagnall and L. Jane Sayle).

Things do get a whole lot messier though, with the looming threat of climate change. A number of collections reference climate stats directly in addition to the terrifying effects already visible to the speakers. ‘1.5’ becomes a refrain for Audrey Brown-Pereira (A-wake-(e)nd), and another poem in her collection asks from the near-future, “where have our children gone […] we who were supposed to go first”. A poem by David Eggleton (Respirator: A Poet Laureate Collection 2019–2022) and another by James Norcliffe (Letter to ‘Oumuamua) both take a single day to be a mini-apocalypse that somehow still keeps going: “Tomorrow is tomorrow, in aroha and sorrow”.

Neither by Liam Jacobson (Dead Bird Books, $30)

Neither was my favourite collection of 2023, and its buzzy cover illustration mirrors the poetry inside. Vivid, offbeat and charismatic, Liam Jacobson (Kāi Tahu) takes a piercing look at the city of Auckland and the hardships it demands of people. His debut collection catalogues the social geography with a prophetic vision in which the vast questions of life and death can appear at any moment among blood-red City Links and mould-frosted ceilings. “The Day Melts Among Me” is a portrait of drinking in a sagging, borer-infested flat with all the luminosity of a religious experience: “at like 5:30/6ish / when the wind is heavy with gold […] and while the mountains of rats / that insulate the walls are still dormant […] about then, when I’ve endured myself enough […] i find my breath heavy with calm”. Thoughtful attention to rhythm, modulation and various forms of internal rhyme means that the poems from Neither have a rich life when spoken aloud. Unexpected metaphors make these poems worth reading again and again, taking you “through the mosh pit that swallows [you] back like vomit”.

The Artist by Ruby Solly (Te Herenga Waka University Press, $30)

The Artist is a narrative in verse that follows the story of one Southern family through three generations. Interwoven with cosmological and historic events, the kōrero includes mātauraka, atua and tīpuna from the author’s whakapapa. The world is sung into being; the first waka arrive; the first people settle; new groups arrive and settle; the first Southern man and woman are born, and later bear children themselves. For Ruby Solly (Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe, Kāi Tahu), the book is “a mahi aroha to the iwi that have shaped my being”, and its intergenerational, oral dimensions nod to storytelling in the tradition of the epic.

With respect to the responsibilities of collective storytelling, the book is clear to position itself as a work of fiction, with each of the four sections opening with a spread of tarot or royal-like cards that introduce characters as ‘players’. Many of the poems echo these small portraits, revealing the characters through defining moments like naming ceremonies, a resolve to pursue carving, or prospects for marriage. An animated, mystical quality infuses the world of the characters and also gives the poet wide scope, such as when the character Reremai falls in love with the goddess Hinepounamu in an awa. Lying together in the shallows,

The air suddenly becomes so thin

that love can fall through it,

can break like a stone

from a great height.

Talia by Isla Huia (Dead Bird Books, $30)

Talia is the first collection by musician and te reo Māori teacher Isla Huia (Te Āti Haunui a-Pāpārangi, Uenuku). It’s a tribute to a friend – the artist Natalia Saegusa, who passed away suddenly last year. Natalia’s artwork graces the cover and reflections on her passage from friend to ancestor reappear throughout the book. The voice of the poet is clear-eyed and thoughtful as the text explores belonging and loss. Numerous dedications at the top of the poems – from literary ancestors like Keri Hulme to artist collectives like FIKA (of which Isla Huia is a part) – show that this poetry is grounded in relationships. A poem for the writer’s wife, “eleven eleven”, ends this way:

thank you / for slipping me

out of the dark / unseen /

back

into the traffic.

At the Point of Seeing by Megan Kitching (Otago University Press, $25)

Megan Kitching’s well-formed verses delight in fulfilling what a reader might traditionally expect from poetry – careful observation, thoughtful reflection and skilled use of poetic form. Many of the poems start with a single point of focus and elaborate outwards, revealing a scene slowly and deliberately. The subjects are often ordinary – a man standing outside a bowling club or a suburban street after rain – but Megan has a way of making them glow with something metaphysical.

One poem, “Memorial Museum”, offers a haunting dissection of how such institutions preserve objects in a kind of purgatory. Shells which had been “prised apart from their lives” now dwell in “marmoreal air” and “a deadalive alpine light”. The tiny worlds that each shell had contained now linger on in an uncertain afterlife – “whorled pools / in gaping sockets” – just as the act of sliding open each drawer of the cabinet is like “hoist[ing] the stream seas / for inspection’” A child standing on tiptoes delights in the mesmerising objects, while an undercurrent of violence raises questions about plunder and death.

Āria by Jessica Hinerangi (Auckland University Press, $30)

Āria by Jessica Hinerangi (Ngāti Ruanui, Ngāruahine, Ngāpuhi, Pākehā) is an autobiographical coming-of-age story. The poet’s journey to reclaiming her Māoritanga is told through a range of forms, from letters to tūpuna and diaristic poems to citations of historical wrongs and visions for the future. The collection is dedicated to displaced or whakamā mokopuna, and throughout the book Jessica offers her own story as an example of how to grapple with all of the double-standards and impossible expectations placed upon rangatahi. Despite the temptation that anyone might feel to make themselves appear a certain way – whether on social media or in a book of autobiographical poetry – this collection is generous and full of humility. Jessica’s choice to continually bring all the difficult and hard-to-reconcile parts of herself to the pages means Āria will be an important touchstone for rangatahi of all kinds.

Tung by Robyn Maree Pickens (Otago University Press, $25)

‘Tung’ is a kind of flowering tree, and an accurate name to sum up Robyn Maree Pickens’ exploration of ecological aesthetics. The collection begins with delicious short poems featuring bats and magnolias before an epistolary poem provides an overview of the poet’s concerns (climate change, injustice, the social history of South Dunedin). This order cleverly gives the reader a sense of solid ground before the book fans into much more playful, experimental territory, including a spread with just the Aquarius sign (︎♒︎) in the shape of the words ‘ki ki’. The collection takes influences from both visual art and poetic traditions, from proceduralism to concrete poetry, and Robyn finds ancestors in people like Cecilia Vicuña and Joanna Margaret Paul that straddle both worlds. What is beautiful, and present throughout, are equivalences between the human and more-than-human. The fate of disappearing butterflies is linked with the struggles of the lonely, the chronically ill or the vulnerable in ways that beg rereading.

Biter by Claudia Jardine (Auckland University Press, $25)

Biter is a witty, erotic book of poems, including Claudia’s own translations from Ancient Greek. Like the killer green typography on the cover and the naked statue (with perfectly centred pecker), it takes well-worn topics of poetry and makes them pop. The opening poem, “Ode to Mons Pubis’” figures the “mound of Venus” quite literally, praising the pubic bone as an embodiment of the goddess of love. Later, a story of a giant octopus from a work called Aelian’s De Natura Animalium XIII.6 begets the poem, “Is it Hard to Follow Your Heart When You Have Three?” “I wait in the dark for you”, the speaker proclaims, and “you crawl up the sewer to me”. A dedication to the poet’s partner at the beginning, and an unmarked epigraph from poet Catullus – “ille mi par esse deo videtur” (I see him as equal to a god) – make Biter seem like a touching and funny book of love poetry. Partway through the book, however, the range of subjects starts widening out to include more mundane or familial things like the speaker’s parents, an overfed Labrador, and the Interislander ferry terminal in Picton.

A-wake-(e)nd by Audrey Brown-Pereira (Saufo’i Press, $30)

A-wake-(e)nd is the third collection from Audrey Brown-Pereira whose self-assured voice traverses topics from climate change to familial love. Tender, prayer-like poems sit alongside humorous or cutting ones that restage injustice, such as this depiction of prime ministers:

muldoon, lange, palmer, moore, bolger, shipley, and clark

kiwi names in your living room with access to your remote control

look nothing like mum and dad

A declaration of feminist power forms an important thread through the book, with the title poem reclaiming the speaker’s agency and another sketching a self-portrait. The poems appear almost like stitches on cloth, with sparse punctuation and phrasing that dots the page. This uncommon but versatile style keeps an openness and sense of breath around the lines, while Serene Hodgman’s cover artwork place the poems in dialogue with a rich field of Pacific arts practitioners.

Transposium by Dani Yoroukova (Auckland University Press, $30)

Dani Yoroukova reads Plato’s Symposium as a party scene where homoeroticism is the standpoint for contemplating the god Eros, and updates theories of queer love into contemporary terms. Phaedrus believes that it’s more admirable to be a Bottom rather than a Top; the goddess Aphrodite Urania is recast as a femme king; and Alcibiades attends pangender mermaid parties. The tone is loud, funny, irreverent, full of swearing and all caps, and fluent in the conventions and discussion topics of online spaces. While the collection succeeds in staking a claim for the relevance of the Symposium as a piece of literature, Transposium faces some challenges in channelling its own energy, cycling through multiple formats (a personality quiz, ‘choose your own adventure’, a Goodreads review, a catalogue of ships) and a cacophony of references (song lyrics, characters from Les Miserables, computer games, 90s movies, contemporary poets, as well as Ancient Greek history and geography).

Respirator by David Eggleton (Otago University Press, $35)

Respirator by former Poet Laureate David Eggleton is a generous, 180-page hardback collection that affirms his role as a poet of the people. His characteristic spoken-word approach uses rhyme and repetition to effect across a wide range of styles, from political satire to incantations and ballad-like histories. An anticolonial sensibility permeates the collection and shows how the ecological, political, historical interweave. “The trees are our parents’ parents”, he affirms in “Generations”, while “Deepwater Horizon” stages a moment of reckoning: “A CEO in a burlap sack / circus-dives towards a barrel of bitumen / from a great height’” There are witty, sharp dissections of societal ills as well as research into the histories and poetries of David’s whakapapa in Te Moana-Nui-a-Kiwa. Together, these two strands give readers something to get fired up about as well as something to learn and grow toward.

ReadingRoom is devoting all week to naming the best books of the year. Monday: the best nonfiction. Tuesday: the best illustrated books. Tomorrow: the best fiction.