Opening Doors in Rockfaces: David Howard’s poetics

Posted: Monday Jan 09, 2017

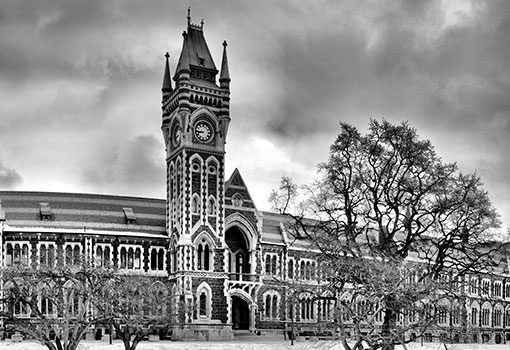

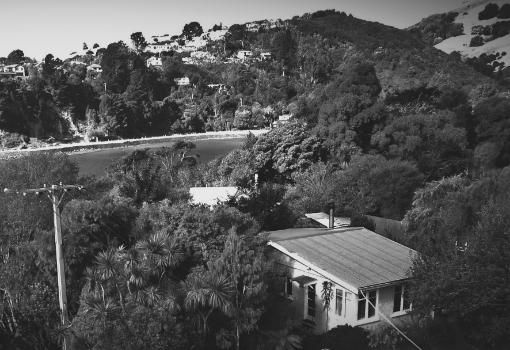

David Howard is a prominent New Zealand poet and co-founder of the literary journal takahē. After 13 years at Purakaunui, he currently holds the Ursula Bethell Residency at Canterbury University. Here he talks about his poetic journey, the interplay of music and words, and his own overseas endeavours.

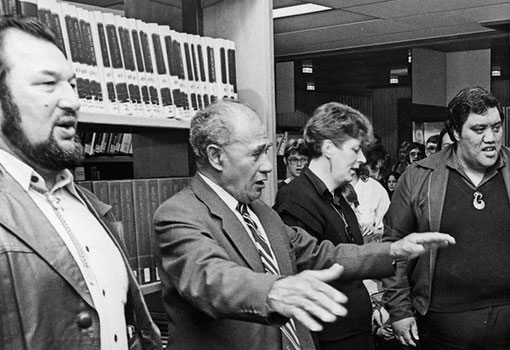

Q1. You are an established masthead in New Zealand poetry, as the co-founder of takahē and the Canterbury Poets Collective. Although I am sure you have relived this moment over and over in prior interviews, could you tell me what launched your first steps into poetry?

My father, Reginald William Howard, read to me as I sat on his lap and wondered; that was how I began to understand language can cast a spell, opening doors in rock-faces, helping ordinary boys fly. He inspired me to write myself out of one of the poorest suburbs in New Zealand, to explore the world that was beyond me until I found the (right) words. As the most focused form of language, poetry let me see more than fiction or drama did. When I discovered poets they became guardians of the self I wanted to become: Arthur Rimbaud, John Berryman, Elizabeth Bishop – they were my mentors, almost my confidantes, as I tried to write.

Q2. Between March and April of 2016, you were the first New Zealand writer to hold the UNESCO City of Literature Writer in Residence in Prague. Your verse drama 'The Carrion Flower' narrated the assassination of prominent Nazi Reinhard Heydrich in Prague – did this prior interest in the city spur you to apply for the residency? How do you feel this period in Prague has influenced your poetry?

Readers can access ‘The Carrion Flower’ at http://www.trout.auckland.ac.nz/press/shebang/shebang_6.html

‘The Carrion Flower’ was one dog-eared calling card; the 2007 setting of my long poem ‘There You Go’ by the Czech composer Marta Jirácková was another introduction. For a reader there is pleasure in lingering over words; for a writer, once the words are set, there is the desire to justify the labour by gaining a readership. Unfortunately the early 1990s, when ‘The Carrion Flower’ was completed, was an unpopular period to prefer the dramatic monologue to the domestic lyric; the former shifts registers in the interests of psychological realism, whereas the latter often orients itself through irony, and when it attempts to shift registers there are bathetic consequences. I always saw irony as a cage rather than a gate.

Yet, 30 years later, the residency in Prague strengthened my commitment to poetry that accepts there is a political dimension, a thrilling one, to perennial questions such as: Is there a God? Are we free? What are the limits of human will and the consequences of its exercise? Can language capture the world?

I do not enjoy emotionally evasive writing; I do not believe it leaves the reader free to enter anything except confusion. Nor do I believe that Bill Manhire is correct when he claims that people don’t want to be preached to. People demonstrably want to be preached to, but they don’t only want to be preached to. A rich clarity is what engages me most in poetry. At 23 I tried and failed to find it in Wellington; at 56 I found it in Prague.

A dark highlight was standing in the crypt of St Cyril & St Methodius, the church where Heydrich’s young assassins died. Time and space condensed so the phantom of the youngster who began when Rob Muldoon was our prime minister paid his respects, 18000kms later, to real leaders.

Find out about the Prague – City of Literature residency programme here: http://www.prahamestoliteratury.cz/en/activities/writer-in-residence-program/

Q3. You have mentioned that during your time in Europe you gave public presentations in Prague, Strakonice, Croatia and Vienna. What did these presentations involve?

The key to a good presentation is the ability to recover your poem in front of an audience, to move through the stages of composition silently on the podium so that when you do speak it is with the enthusiasm, the urgency, of making rather than with the calculation of ego.

Select the material for the projected audience; order the poems so they follow an emotional arc, then frame them with the briefest of introductions and enunciate clearly without undue emphasis. This is a poem, not a slam caricature.

I came closest to realising the above ideal in my reading at Split as part of Goranovo proljeće 53 and then at my farewell presentation in Prague on 24 March 2016. The classroom dynamic at Strakonice, where I addressed 50 attentive teenagers, meant I was not confident enough to go deep – and I suspect that was an error on my part, because their youthful intelligence was a fierce one hungry for detail. At the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, under the direction of Esther Dischereit, we workshopped my grid poetry – one of the ways I mediate between the poles of my peers Michele Leggott and Jenny Bornholdt. There it was possible to interrogate the political implications of narrative, to open up the poem so it filled the room with multiple voices that informed and were informed by the students.

Q4. Poetry and music have a long and intertwined history. In 2004, your long poem There you go was set to music by prominent Czech composer Marta Jirácková More recently, you have collaborated again with Jirácková, who has scored your poem 'The Impossibility of Strawberries'. How will audiences be able to experience this collaboration?

In November 2016 the Morgenstern Ensemble will premiere 'The Impossibility of Strawberries' in Prague; the setting will be expanded from soprano and piano to include the flute, in response to the ensemble’s commission.

https://morgensternensemble.wordpress.com/gallery/#jp-carousel-49

Q5. I know that you have had a long career in pyrotechnics and special effects, and of course your work has been set to musical scores – how do you feel about poetry conveyed through media other than the printed page? For example, Dunedin poet Emma Neale’s poetry projected on a wall in Krakow, Poland as part of a UNESCO City of Literature Initiative in 2015.

Printed, the poem has a home but – as Emma’s success shows – it can travel a long way from that home and grow while doing so. I have been attracted by collaborations for decades because the defense mechanism of habit is challenged by them. And I delight in poems that escape the page, such as the sculptural incorporation of Ian Hamilton Finlay’s memorial to the victims of Nazi courts in Vienna. It disappoints me that the texts of New Zealand writers are not often part of the architecture of urban spaces; temporary projection, yes, but why not paving stone or wall more often and for generations? The Wellington walkway and the Octagon plaques are well and widely regarded. Inscription on public buildings is cost-effective, elegant, and helps citizens and visitors alike reframe the place memorably.

Q6. Now, so soon after your two-month residency in Prague, you have been granted a one-month residency in Croatia next year. Congratulations! How did this come about?

It is an instance of the City of Literature network rippling across borders. If Dunedin had not backed my application, if Prague had not given me the nod, then I would not have been able to read at Goranovo proljeće 53. One night my Croatian translator, Miroslav Kirin, took me aside: ‘Apply!’. I enjoyed working with Miroslav and his country(wo)men Dorta Jagic, Mateja Jurcevic, Sonja Manojlovic and Marko Pogacar. I wanted to expand my understanding by composing a sequence of poems set in their country – poetry is not so much a leap into the unknown as a wander through the half-known. I chanced my arm and my aim proved true. Now the task is to write beyond my comfort zone, using my innocence (a poem is a curious child) to give authority to the work.

Readers can learn about David Howard’s Croatian residency at this address: http://kucazapisce.hr/en/hiza-od-besid/