Short story: The Islands of Arthur Trimble

Posted: Tuesday Apr 04, 2023

"He imagines the rattling windows of his bach": a sad seaside saga by Majella Cullinane

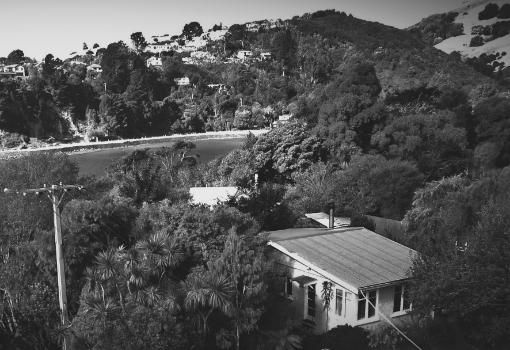

Màiri watches him as he walks down the hill next to her house. The man appears gradually – first his head covered in a tweed cap and earphones, then the unkempt hair and beard, and finally his hunched shoulders and body. A small black dog walks behind him, off-leash. Today he’s wearing a long overcoat and carrying his customary black umbrella. She hasn’t met him and knows only that he lives in an old bach above her house. When she passes him in town, he keeps his eyes fixed on the path and doesn’t say hello. She’s not sure if he’s rude, in his own world, or extremely arthritic. Màiri likes to give people the benefit of the doubt, and given his posture, she chooses the latter.

She dresses her little girl Ròs in a coat, hat and scarf and heads out for a walk. Recently a mother in the kindergarten group told her she was becoming a familiar sight – the petite woman walking the Shore Road pushing a buggy. Another woman wanted to know if she was all right, was she not lonely walking by herself? Màiri wondered then if driving a car somehow contained loneliness more, concealed it behind upholstered seats and child-locked doors. But she didn’t say this, only that she enjoyed the exercise. Nor did she say that walking broke up the day, the nap times, the meal times, the waiting for her husband to return from work.

Arthur has noticed the young woman watching him as he makes his way to town. His neighbour Edna mentioned the new family had only recently moved in, that they were from Scotland. When he’d first moved into the bach she’d brought him a lemon meringue pie to welcome him. She remembered his parents she’d said. Wasn’t his father a teacher, his mother a blonde, very pretty? While Edna spoke, Arthur had looked at the sea from his small window, remembering a time his father had taken him out on a kayak when he was five or six. It had been a gloriously hot summer that year – the sky cloudless and blue; each morning the pōhutukawa on the front lawn filled with a chorus of cicadas and tūī and blackbirds. His mother waved from the shore, her hair wet and curled below her jawline, her body long and lean in her red bathing suit. The sun was hot on their faces and arms. When Arthur looked over the side he could see billowing sand, small pieces of Eucalyptus bark and leaves floating past them, and on the rocks further out, pāua shells and kelp swaying in the waves.

It was only when Edna had stopped speaking for a moment that Arthur noticed her looking at him strangely, asking him for the second time what he’d said his name was again, why he’d come back? Arthur had offered crumbs – an island in Greece, yes, teaching English, yes, retired, yes, just turned seventy. He'd thanked her for cake and told her he needed to head out .

*

The beach is empty today as Màiri settles the buggy next to the small wooden steps and applies the brake. She lifts her daughter out and slips her socks off, watches her as she waddles to the water squealing with pleasure. For a moment she looks back at her mother and then stumbles. She lifts herself up and hesitates. Màiri takes her outstretched hand and tells her daughter to wait a minute, explains that she needs to take her shoes and socks off too.

The water is cold when they dip their feet in. Her daughter smiles, oblivious to the temperature, to the wind picking up again from the south. A few more steps and she curls her small body over the waves, her fingers strumming the water’s surface. She lets go of her mother’s hand then and runs back to the sand. She points at the buggy, at the blue and yellow bucket and spade under the seat. Màiri fetches it, and her daughter starts digging, flinging the sand behind her.

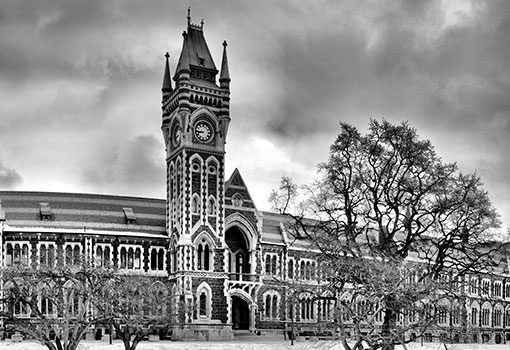

Màiri looks out towards Kāpiti island, its neat outline partly obscured by a low mist this morning, a swathe of grey cloud lingering between Cook Straight and the mainland. She’s heard there’s a boat that leaves from the next town daily, but her husband James would probably refuse to go. He dislikes boats and can barely swim. It had been difficult enough to convince him to move away from the city. She’d had to remind him again she’d grown up in a small seaside village, and if he’d decided he couldn’t miss out on a professorial position in New Zealand then he could at least compromise by living closer to the sea. After a month in Wellington, she suggested they explore the smaller seaside towns nearby. When she took her first walk along the Kāpiti coast, she knew this was where she wanted to live, and the commute was only half an hour. In some ways the village reminded her of Pittenweem although it had no cobbled pier, and not nearly as many seagulls to rend the air with their insistent racket.

If James doesn’t want to go to the island Màiri thinks, perhaps she and Ròs could catch the train and go themselves. It would take less than a half an hour on a good day she reckons. Considerably shorter than swimming, which reminds Màiri of a story she’d read in a local history book, about a Māori woman who’d swum from the island to the mainland with her daughter strapped on her back when her tribe spotted invaders approaching from the north. Màiri couldn’t imagine being so brave, mustering the resolve to swim those five miles. To think that at any time the waves might submerge her and Ròs.

“Mama, Mama,” Ròs calls, holding the long spade in her hand, her bucket half-filled. Màiri picks up the bucket and takes her hand.

“We need water to make a proper castle Ròs,” she says. “Come on.”

*

Arthur has days. A day to do the weekly shopping, a day for the library, a day for cleaning. Once a week he squeezes two outings into one day. On Wednesdays he visits the local bookshop, not much bigger than the size of his bach. He exchanges a few words with the local writer that owns it, a portly man with straggly white hair tied in a pony tail and a high-pitched voice. They discuss the owner’s latest book acquisitions, the weather, if any new history titles that Arthur might like have come in. On his way back from the bookshop, Arthur goes to the local church. Not to pray, but as he would describe it to ‘muse’. He likes the neat symmetry of the altar, the tight row of pews with narrow upholstered kneelers, the stained-glass windows that depend on the angle and quality of light for their beauty. Not as grand or ornate as a Greek Orthodox church with its grave icons, its long candles like white, flowerless stems, but to Arthur’s mind preferable for its simplicity.

Today he sits in the third pew from the back and thinks about the Scottish woman and her child. Arthur has pictured himself in her kitchen, her small body arched over a teapot as she pours him a cup of tea into a coffee mug. The young woman reminds him of his daughter Calliope, who had left with his ex-wife for Athens twenty years before. Calliope who he’d grown estranged from, who had her own daughter, a grandchild he’d never seen.

He’s struck by the autumnal light as he leaves the church – a similar quality of light that drew him to Greece forty years ago; the sun-bleached terracotta tiles that made the sky seem bluer, clearer, the light that warmed the eyes and stroked the skin as if it were chiffon. The same island Odysseus had travelled from, the one Arthur Trimble had chosen for that reason, a love of Homer’s Odyssey. Ithaca.

*

Arthur looks out into the night, at the ocean brimming through the mouth of Cook Strait, and along the edges of Kāpiti island. It is a night not unlike a summer years before, when he’d woken at midnight and crept out of the bach for a swim. The twelve-year old Arthur had lunged into the sea then, and despite its coolness savoured the dark indigo waves caressing his arms and legs as he swam out farther, deeper. What he remembered most, more than the cold water on his skin, the salt in his mouth and tongue, was floating on his back and gazing at the whorl and cluster of stars, shimmering like a billion tiny pins.

Arthur turns off the reading lamp and makes his way to his bedroom, Pepper following behind him.

*

At the shop Màiri puts a carton of milk and a packet of biscuits on the counter. She’s relieved it’s the shopkeeper’s son behind the counter today; a man in his early twenties with gelled, spiky hair; a mobile phone propped under his chin. He acknowledges her by raising his eyebrows and then keying in the numbers with his fingers. Better this anonymous exchange than the shopkeeper owner who comments on her purchases. “More biscuits love, you’d want to watch that sweet tooth of yours.” She’d preferred him when he was frosty and business-like. But then no doubt he’d heard that she’d become a local of sorts and had begun to discuss the weather, and more lately her buying habits.

Màiri is leaving the shop when she sees Arthur across the main street. He doesn’t have the dog with him today. The railway bell starts ringing, the signal lights flashing red, and Ròs cries “train, train”, so they leave the buggy outside the shop and walk to the white picket fence next to the tracks. Arthur picks up his pace as the train passes, hurrying through the railway gate and across the line to the platform. Màiri wonders if he will make it in time so she and Ròs wait until the train pulls away again. She’s pleased when she sees the platform empty, and wonders where the old man could be going this morning. She picks up Ròs and they walk back towards the shop. Her daughter refuses to go into the buggy so Màiri takes her hand and pushes it slowly up the path, past the church and village hall, knowing it will take twice as long now to get home, to enjoy a few biscuits and a milky tea while Ròs naps.

*

That evening Arthur rubs his knee, and winces. Despite taking an anti-inflammatory his body aches. Better to have missed the damn train and waited fifteen minutes than this pain he thinks. He hobbles to the kettle and makes himself a pot of tea, gives two biscuits to Pepper and places four on a plate for himself. Arthur takes a biscuit from the plate and dips it into his tea.

*

Màiri looks out to sea, at the brooding metallic grey waves charged with white caps. Her husband has just called to tell her a tree has come down on the main line, and rather than wait a couple of hours for a bus, he’s decided to stay overnight with a work colleague, that he’ll see her tomorrow evening.

She’s about to close the curtains when she sees the old man; his head hooded and bent like a monk as he shields himself against the heavy rain and wind, cradling a large bulge under his coat. Instead of turning left towards the village as is his custom, she watches him take a right and continue along the path, and up her driveway. She moves towards the front door, waits for a knock, feels her pulse quicken even though she’s expecting him. Her daughter Ròs wraps her arms around her leg and looks up.

“Mama, knock, knock,” she says smiling.

“Good evening,” the old man says, “What terrible, terrible weather. I live in the bach up the hill. I’m very sorry to bother you, but my dog Pepper isn’t well, and my neighbour Edna mentioned you were a nurse.”

“Aye, a nurse, but not a vet, Mr?”

“Mr Trimble. Arthur Trimble.”

“Still, you’ll be familiar with medical matters. I’d take him to the vet, but the radio said the trains aren’t running, and it’s too late in the day now.”

“Please, please come in out of the weather, Mr Trimble. You can lay him down here by the fire. How long has he been like this?”

“He hasn’t eaten for a couple of days.”

“Well, I’m very sorry, but I really don’t know much about animals.”

Màiri takes the blanket off the dog, and Pepper cranes his neck and looks at her without raising his head.

“Mama, Mama, doggy.”

“Yes, doggy sick, poor doggy,” Màiri says.

‘What a beautiful black coat,” Màiri says as she strokes the glossy black hair and long ears. “What kind of dog is he?”

“A Spaniel.”

“How old?”

“I’m not entirely sure. I got him from animal rescue when I first arrived. They said he’d been abandoned, and they guessed he was about twelve years old, so I suppose he’s old for a dog. I took him to the vet about six months ago. He’s very deaf now and I should probably put him down, but I haven’t the heart.”

“Well, it’s nice and cosy by the fire Pepper, isn’t it? Would you like a cup of tea Mr Trimble?”

“I don’t want to be any trouble; it was foolish of me to bring him here.”

“Not at all. Just let me put my wee nip Ròs to bed.”

Arthur looks around the living room, at the firelight reflecting on the large bay window behind the couch. The curtains are partly drawn so he cannot see past the garden fence, or across the road to the beach where the sea is tossing and turning like a restless sleeper. When Màiri returns he will ask her if she’s been to Kāpiti, if she’d heard the story about the woman who swam to the mainland with her child on her back. He will tell her what his mother told him once when he was a boy, that the swimmer might have been an ancestor.

Arthur strokes Pepper’s fur, rests his hand against his body, feels the dog’s heart pulsing for a moment. He imagines the rattling windows of his bach, a latch unhinging itself in the wind, and the rough, wild air scattering his journal all over the houses and electricity lines, and down onto the beach where his words will turn inky and smeared.

He takes a biscuit from his pocket and gives it to Pepper. At first the dog refuses it, turning his nose towards the fire. Arthur tries again, and this time Pepper takes a bite, then another, until he has greedily eaten the entire biscuit, his black eyes reflecting his owner’s face back to him, hoping there will be another one to follow.