Short story: Broderick and Riley, by Owen Marshall

Posted: Tuesday Feb 13, 2024

Two lifetimes of two Kiwi men, told in 1609 words

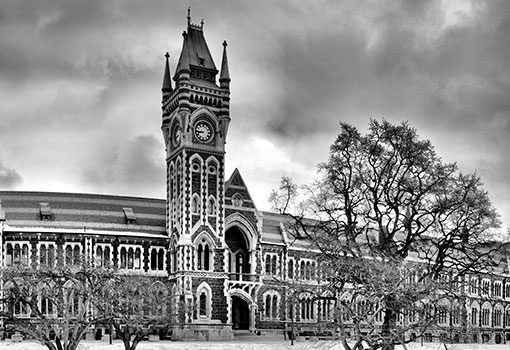

Short story: Broderick and Riley, by Owen Marshall (newsroom.co.nz)

Broderick and Riley met five times during their lives, a total of less than nine hours, although they wouldn’t have been capable of such exactitude. They were not friends and had little consciousness of each other despite the occasions on which they interacted by whatever fate, or chance, you wish to believe in.

They were first together at the children’s playground in the civic gardens when Broderick was seven and Riley six. Broderick’s parents were some distance away, looking through the glasshouses. Riley’s folk were sitting on a green bench, his father with face raised to the sun, his mother scrutinising a stain on her linen dress. The weeping willow drooped in full foliage and swayed gently in time with the breeze. A mallard duck was querulous because no-one offered bread scraps. The boys found themselves at one of the see-saws and not having companions of their own, began a cautious and silent co-operation. First Riley climbed on, then Broderick reached up, pulled down and clambered on. They oscillated for a time, still without speaking, for they were strangers. Not only was Broderick older, but he was heavier and had to thrust his legs strongly from the ground to get his turn in the sky. He became aware of his superiority and so despised Riley on the other end of the see-saw. He stepped off abruptly and Riley’s end came crashing down. Riley’s face hit the iron hand grip which chipped one of his front teeth. He cried loudly in both anger and pain, but Broderick jogged away taking no responsibility. Both Riley’s parents came quickly to comfort him. His father said they’d have ice-creams as consolation, his mother hugged him and said thank goodness they were his baby teeth. Broderick stood partly hidden beside a rocket ship and watched them. He hadn’t intended harm, but was intrigued, rather than feeling any guilt as a consequence of his action.

Eleven years later Riley and Broderick were in opposing college first XV rugby teams. It was more than just the annual inter-school fixture. The final of a recently introduced secondary schools tournament and taken seriously, not only by the boys. School mana and parental pride were involved as well as the self-respect of players, some of whom had dreams of representing the sport at higher levels. Frost was white on the field and at scrums and rucks panted breath ascended in the still air, visible and drifting. There were many onlookers, including Riley’s parents and Broderick’s mother. She was not avid concerning sport, but loved her son and was standing in for her husband who was stranded and angry in Wellington because his ferry crossing had been cancelled.

There had been a reversal in their respective weights since the boys rode the see-saw, but both Broderick and Riley were hefty and muscular, one a lock and the other a prop. They were on the cusp of manhood, fit, strong and delighting in the smash and grab the sport demanded. They didn’t know each other’s names and had no wish to do so, yet shared the close physical familiarity of a contact sport, butting their heads, pulling at each other’s arms, clasping thighs in a passion of obstruction. Both earned the commendation of their coaches, but it was Riley who had the additional satisfaction of a win. He had also a swollen and bleeding eye socket from Broderick’s left boot in a second-half ruck, although neither was aware who was responsible and it was entirely accidental. In a school magazine photograph of that year, Riley is one of the players with a hand on the cup.

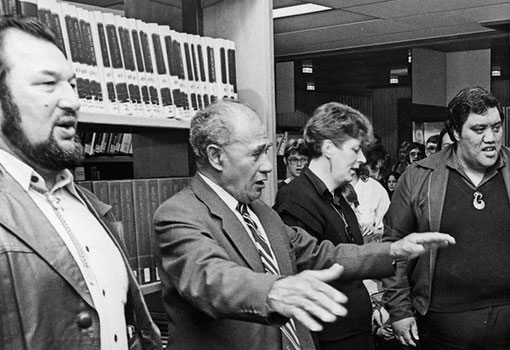

Broderick and Riley were first introduced at a Young Businessman Of The Year event, the only time they heard each other’s names. Riley was 33 and Broderick one year older of course. Riley wore a grey jacket with a pink shirt open at the throat. Broderick wore a light suit, a striped tie, and talked fluently of the innovative scientific equipment his firm had developed for the genetic improvement of livestock. Riley gave a screen presentation of the value and nature of distribution hubs, and despite the prosaic nature of such a business his commentary included asides that occasioned some amusement. Neither of them received an award, or placing, and within a few days they had forgotten each other completely, busy with their respective enterprises which had little in common. They were not to know that on the night their preferences for wine and mains had been the same – the dry riesling and poisson du jour. Whether that has any significance at all there is no way of telling. Both men were accompanied by their wives, but the couples were not seated within a conversational distance so Esther and Mia didn’t meet Had they known they both had language degrees and shared an enthusiasm for orchids, they may have made an effort to do so. The Young Businessman of that particular year was much later convicted for ponzi scheme fraud, but that’s by the by.

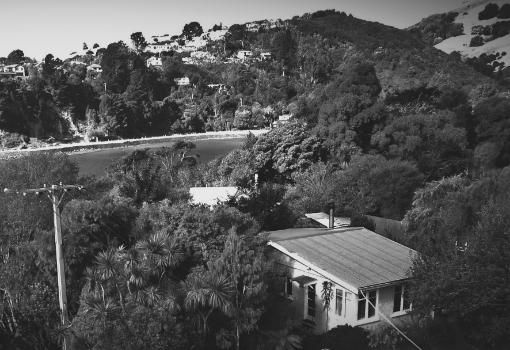

The fourth meeting between Riley and Broderick took place 15 years afterwards at a farmlet 19ks outside the city. A little after mid-December and they were there to buy Christmas trees. Juvenile pines were on sale closer to home, most offered by charity groups, but on the farm a purchaser could stroll the rows, observe symmetry, calculate the height, and make an individual choice, which would be cut on the spot, fresh, glitter green and without wilt. A good many people wished to make such choice and various vehicles came and went, stirring dust from the unsealed track and the turning circle by the shed. Broderick drove a BMW saloon with a small trailer, Riley a Mazda 5 SUV. It was a hot day and both men were casually dressed which was unusual, for they headed successful enterprises, worked long office hours and had executive images to maintain. Riley wore stressed jeans, short sleeved white shirt and designer sneakers. Broderick wore knee shorts, blue T-shirt and Tuscan sandals. They arrived at much the same time and due to that coincidence found themselves briefly quite close together, walking among the Christmas trees that were not much taller than themselves. A sky blue and fathomless, hills pulsating in the distance. Broderick had reclaimed the weight advantage he had all those years ago on the playground see-saw. He was not a fat man, too much aware of self image for that, but he was tall, powerfully built, and since Mia had left him for a journalist he had eaten out with greater regularity. Not that Riley was much behind in stature, also a big man, but one who found time for the gym, encouraged by Esther. He was almost completely bald though, Riley, and to avoid the sun’s assault he wore a hat rather like those favoured by lawn bowlers.

Despite the shared intention of selection there was no conversation, or recognition, between the two, minimal awareness as strangers, and the only passing eye contact occurred when Riley’s SUV on departure briefly blocked Broderick’s way as he walked to the shed to make payment for his Christmas tree, and two others as a donation for the Salvation Army. Broderick’s divorce had a chastening effect and he’d become more aware of those who suffered misfortune. His Christmas tree was to be erected at his daughter’s home.

The last time our two protagonists were together it was night and they were travelling between cities in a bus. An unusual form of transport for both. Normally they used their own vehicles, flew when possible, and favoured taxis when necessary rather than buses. On this occasion however the plane had been turned back because of fog, and the alternative was a lengthy and tiresome journey by road. Riley was alone, on a trip to join a selection panel for the appointment of a senior executive. Broderick had remarried and was accompanied by Anna his wife on their way to visit her ailing father.

Both men were content with their lives, despite the temporary inconvenience of their situation. Healthy, wealthy and happily married with settled families, they had no reason to be displeased. The bus had been specially chartered by the airline and carried only its dispossessed customers. Riley sat towards the front, beside a snoozing, elderly man whose breath smelt faintly of peppermints and whose hands were like the talons of a hawk. Broderick sat towards the back with with Anna, who was fragrant with French perfume and talked of new heat pumps that she said made no noise at all.

Rain began as they travelled over the hill road. Not heavy enough to be audible within the bus, but a drizzle that gathered on the windows and caused a jewelled and shimmering fragmentation of the few lighted places they passed. Enough also to distract the driver so that he failed to gauge one of the tighter corners and the bus rolled over the bank into the rocky gully. A well-known woman equestrian proved a hero by contacting the emergency services and going up to the road with a torch to wait for them. A Wellington chiropractor also distinguished himself by effective first aid to the injured before assistance arrived. Five people died, and Riley and Broderick were among them. Anna was fortunately unhurt.

The bodies of Broderick and Riley were taken away in the same ambulance, side by side, with their faces turned towards each other. Fitting in a way, for though unconscious of it then, or any time before, their lives had shown brief moments of synchronicity.