Short story: Hitch, by Emma Neale

Posted: Monday Aug 05, 2024

A gothic masterpiece by the great Emma Neale

Short story: Hitch, by Emma Neale (newsroom.co.nz)

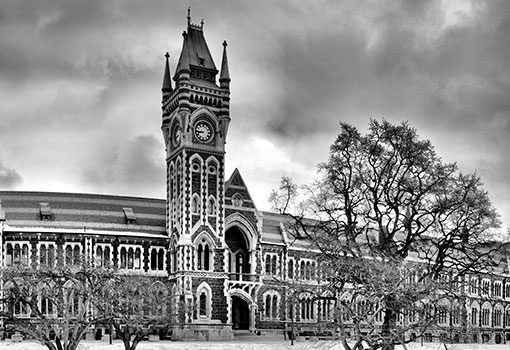

We were driving along State Highway 1 at night, after visiting family who lived out of town. Even as we travelled nearer the city again, the highway was spookily deserted. It was a week or so after our national lockdown lifted, and I wondered if people across the region were still hunkering down, experiencing the foreboding I’d felt the very first day we were allowed beyond our neighbourhoods. That day, among dozens of other people out walking along St Clair beach, beside the rolling immensity of the South Pacific, I’d felt exposed: nerves as raw to the elements as grazed skin. Days later, the sensation of freedom trickling back after weeks of isolation remained unexpectedly disorienting, even discomforting, like frost-nipped fingers tingling with red thorns of heat as they slowly begin to thaw.

Perhaps this undercurrent of unease sharpened the jolt when, like a flare, a figure split the darkness ahead. Our headlights had caught the yellow reflective jacket of a solitary figure hovering at the roadside, next to a broken-down car.

After larkspur-blue skies all day, the temperature had plummeted the instant the rugged crags of the Silverpeaks hid the sun. As we got closer to the driver, we saw his hands were tucked into his armpits, his shoulders hunched to his ears.

“We should stop and see if he needs help,” I said to my husband.

“He’ll be fine,” Rick answered. “He’s prepared. He’s in safety gear.”

“But it’s freezing out there!” My voice pitched unnaturally high. “And someone stopped for us.”

*

I meant the time, over a year ago, when I’d been the only adult in the car, ferrying three children down the same route. After a long, relaxed Saturday beachside picnic with friends up the coast at Karitane, we’d set out homewards just before dusk. On our trip back towards the city, nightfall arrived so swiftly that it reminded me of that Katherine Mansfield line: the one that starts, “There was no twilight in our New Zealand days . . . “ As I tried to recall the rest of the passage — something about the “half-hour when everything appears grotesque” — we saw someone heading in the opposite direction. I dipped the headlights. There was a sudden bang, as if our undercarriage had hit something. Black, toxic-smelling smoke billowed from the car’s hood.

Jake, our teenager, swore. I let that go, even though it was in front of his little brother, pulled the car over and said, “We need to bail. Get out, quick! On the passenger side. Away from traffic.” All of us scrambled, running from the car in case it burst into flames, movie- style.

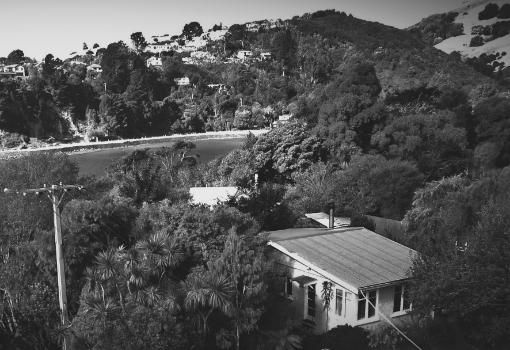

This far south in Te Wai Pounamu, even in late summer, the air was chilly after sundown. Despite our jackets, we ended up shivering on the roadside, the two teenagers — Jake, and his friend Lani, with us for a sleepover — sidestepping and jiggling to try to stay warm; Lani tucking her long, loose hair around her neck and under her collar like a scarf for extra warmth. Our eight-year-old, Ewan, pressed in close to me. His teeth chittered as he talked; I realised he might actually be shaking from delayed fright. I took off my coat, gave it to him, hugging him till the chattering stopped; then as I hunted around for my phone, guessed it must have fallen out of my handbag somewhere in the car.

We were on a rural stretch of the motorway: nothing but farm paddocks and scrubby remnants of fragile alpine forest on either side of us; yet there was fairly frequent traffic. As driver after driver careened past, I thought things through aloud. “When the smoke dies down, I’ll head back to hunt for my mobile. Then I’ll call for help.” It was like whistling in the dark, trying to reassure both myself and the children An old station wagon travelling south slowed down and drew up alongside us. Packed to the gills with bags and bedding, with a fabric lei, a blue god’s eye bead necklace, worry beads, feathers, and a lanyard of some sort dangling from the rear-view mirror, it also held two sunny, tangle-haired young women. The passenger cranked open her window, and in a cheerful sing-song she asked if we were all okay. We told them what had happened, and they offered us blankets, and even some baking. “Mum made us muffins for uni,” the driver said, with fond amusement. The passenger, who might have been her sister, loaned me a cellphone to make an AA call. I got through to the helpline relatively quickly but the woman who answered said the tow truck would be at least an hour. They only had one guy on night shift; he was way out at Green Island at the moment, on the other side of the city. Oh, and his truck only had room for two extras in the cab.

The students, no hesitation, offered some of us a ride home. I had to make one of those rapid internal parental judgements about who was safer where. Should I keep Lani out here on the motorway in the glacial dark, or do I send her away with strangers? What would her parents think? Little Ewan’s freaking out, but if I sent him home with her, and kept Jake here, she’d need to babysit. And if I …

I turned to Jake and Lani. “Do you two feel okay about catching a lift?”

“Totally!”

“Ioe, awesome!” They loved the “cool old retro” music the students were playing on their stereo; the car would be warm; the muffins looked delicious. I made a dash back to our now smoke-free Toyota to scrabble around for my phone. The students and I exchanged numbers so that eventually I could return a blanket we borrowed, which my eight-year-old was now wearing like a cape. I waved the teenagers and their rescuers away.

Beyond the road edge, flax, manuka, gorse and broom made dim shapes: unsheathed swords, crouched haunches, bowed heads, curved spines. Each time the occasional ute, van or car roared by, we’d be spot-lit, the glare of headlights seeming to intensify our isolation and the penetrating cold. Ewan started to talk about how we might get murdered out there in the dark.

Memories flickered in my head like broken lights. When I was just a little older than him — only by a year or so — there was a news story in the early evening slot my parents often watched when we lived in America. As the bulletin unrolled, the terrified knowledge it gave me felt like a kind of losing grip. Poster-thin blue and white pieces of reality threatened to peel off and blow away, to leave a swirling chasm beneath.

The report was about a young girl in an unhappy home situation who had been trying to get a ride somewhere on her own. She accepted a lift from a stranger because she thought a man old enough to be her grandfather would be safe.

The visceral horror of what she went through that night seemed so extreme, even when I recalled it all these decades later, that I wondered: had I misremembered this? Was it a sinister urban legend, a macabre, contemporary Little Red Riding Hood, evolved to discourage girls from wandering and travelling on their own?

Yet I could still see the young Californian hitch-hiker in my mind’s eye, with her long, wavy, dark hair, her serene and gentle face, and the reminders of the savage violence from that night: her pale prosthetic arms, their metal hooks. I’ve looked up her story since: it was not a legend. The young girl, Mary Vincent, is still alive. Her torturer, thank God, is not..

This chilling story; others in the news over the years; memories of one man’s hands at my throat; of an angered boyfriend jabbing between my legs with a broken branch; a stranger breaking into the room where I slept; another forcing me down onto a bed, too strong for me to roll him off — all filled me with charged dread, out there in the bitter, motorway dark.

Yet my job as a mother was to lead Ewan out of his breathless, tightening spiral. “You know what, sweetheart? The only people who have stopped, out of dozens driving by, just gave you a chocolate muffin. That’s exactly the opposite of what you’re scared about.”

He buried his head in my chest, and I rumpled his hair. “It’s okay, little man. Hey, have you noticed the stars? You can see so many out here, away from the city lights. They’re amazing.”

He peeped at the sky. “They look like icy dust.” He shuddered. “We could die out here. We’d be frosted bones by the morning.”

“We’re going to be okay, Ewan. The tow truck will be here soon.” I encouraged him to tread with me a little way up the berm that was wild with grasses, nettle and other weeds, so we were even further out of the path of any traffic. While we were shuffling towards the farm paddock’s wire fence, a 4WD Hi Lux with a cage trailer barrelled past. In the distance, it started to do a U-turn right in the middle of the highway. My spine braced. What if someone else, inattentive or overtired, hurtled up out of the dark, unable to stop in time? The Hi Lux doubled back and drove past us again, stopping up some way ahead of our abandoned car. A strong, solid-looking man in reflective coveralls got out and strode towards us.

“Someone coming for you?”

My mind jammed on his phrasing.

“My wife said we had to stop,” he said. In the pitch dark and at that distance I couldn’t see any passengers in his vehicle, but something warm, pliant, in the way he said wife felt like the lowering of a gun.

“Oh, thank you,” I said. “Yes, I’ve called the AA. They said they’ll be here as soon as they can.”

“Right-oh. Not sure what else I can do for you, but here,” he held up a lime-coloured fluorescent vest. “You could do with this. I’ll need it back for work so I’ll give you my number. Assume you live in town?”

I said yes, took his number, thanked him again, profusely. He said a no-bother “Che- roo,” in a laconic, South Otago way. After re-wrapping the blanket like a toga around Ewan, I slipped the luminous nylon vest over his head and settled it across his shoulders. It came almost to his knees, but he did a quick little sideways dance at being the one who got to wear it.

After the Hi Lux and trailer sped off, I said, “People have been really kind. Aren’t we lucky?”

“Mum,” Ewan said, in that seamless, senior tone kids can deliver with such devastating disapproval. “Why do you do that thing where bad stuff happens and you say we’re lucky? Our car just caught up on smoke, and we’re standing in the freezingest middle of the night.”

Tomorrow promised a storm of mood swings if I couldn’t get this boy to bed. I checked my watch. It was nearly ten o’clock. All I could do was try to distract, by prattling happily. My imagination was fried, though: fried and pinned to our immediate situation. I scraped around in my head and all I could come up with were anecdotes of the other two occasions I’d caught rides in big trucks. Ewan was in a dragons phase, though; my big-rig accounts held no dragons; he was flatly unimpressed.

When the AA tow truck finally appeared, I woo-hoooed! and squeezed Ewan tight. He jumped up and down, with zero relief or gratitude, just reiterating, “It”s so cold!”

A stocky, bespectacled man swung down from the towie’s high cab with a genial weariness. He told us we were right to be waiting on the roadside, not in the car, despite the temperature. Too many people, he said, had been killed by other drivers slamming into stranded vehicles they hadn’t seen until it was too late.

I still had to ignore a prod of apprehension over getting in to the truck. What other options did I have?

As it happens, our conversation was low-key, a bit dutiful: but the driver genuinely seemed to like helping people. My first impression — that he moved with the achy erosion from working long, physically-draining shifts — lightened when he talked about his young daughter, whose photo was on the dashboard. He sat up taller, glanced over at me now and then, gave a bouncing laugh about how much kids cost. His daughter loved kapa haka, netball, ice-skating, Taylor Swift, and ever since she turned thirteen, “That Teeks,” he said. He fell into a slightly wistful reverie then, but he got us safely home, offering good advice about auto-repair shops, and left our wiped-out car in the driveway for us to deal with later.

The kindness of strangers, I thought, as I collapsed into bed later that night. It’s a thing. What was I so worried about?

*

As my husband drove past the shivering man marooned on the highway, every detail about that other breakdown pushed into my chest.

“Rick!”

“Okay.” He slowed and pulled over. “I’ll have a word.”

In the dim light, and watching Rick’s profile, I couldn’t quite read his expression. Was he pissed-off, wary, preparing himself for messy social complication, or a little sheepish that he hadn’t felt that Samaritan impulse himself? Whichever it was, I cupped his knee to thank him for stopping. He covered my hand and squeezed before he stepped out of the car.

While he walked back to talk to the guy on the roadside, the children and I went over the story of that time we were rescued, trying to confirm particulars: the smoke was black, right? There really was a bang? And the long-haired, bubbly students, with Pulp and Oasis playing on their stereo, and the muffins with chocolate and toffee chunks, remember them?

Soon Rick and the stranded man were at our car, climbing in. The stranger was slight, his face stubbled. He was shorter than both Rick and our eldest son, and younger than me and my husband: his hair brown. Ripe brown, it seems to me, now that silver spiders at my temples. Do young people know how colourful they are, how vivid, even when they’re a little scruffy, a little worn around the edges after heavy days and screwed-up nights?

“Real good of you, thanks,” the guy said, atonal. It made me think of thin metal foil rolled out, an unmarked sheet.

“All right,” my husband said, as if he understood a plan of action — not as if he was saying, happy to help. Both kids were sleepy after the day’s out-of-town trip, had to have it explained that they should move over, to make room for our passenger. Even then it took them a few beats to actually do it. It looked like reluctance, not drowsiness, and I felt a pinch of frustration. Manners, I thought, and we’ll discuss it later. They also had to be told to gather up their detritus to make space: hoodies, single shoes, an open bag of corn chips, Ewan’s craft book, 100 Paper Dragons — which was a bit of a rip off. It was basically a book of origami paper, printed with different skin, feather and scale patterns: the “dragons” were just paper airplanes. We’d made Ewan bring the book along to try to keep him off screens. Jake scooped up half a dozen planes Ewan had made earlier; Ewan, overtired, started to fuss about him bending the noses. Jake pulled his woollen beanie down over his ears: makeshift soundproofing. “Dude,” he said irritably. “Not cool.”

“Ran out of petrol,” the guy said, as he put on his seat belt. “Forgot to fill up after my shift. If you run me into town and drop me at the north-end BP, I’ll be set.”

“Yup,” my husband said.

The following silence quickly felt too stiff, too tight.

“Whereabouts do you work?” I asked, twisting around a little in my seat.

“Macraes. Fix up the trucks and mine machinery and all.” His voice was flecked both with splintery pride and a glint of hostility.

I felt myself turning this over in my mind, the way I might probe a broken-edged toffee in my mouth, testing its roughness. I tried to find the link between running out of fuel and being a mechanic. As I hunted around quietly for some other small-talk, the smell of alcohol, like a rotting tropical flower, pushed into the front of the car. It hit me with something I’d completely overlooked in my urgency to get Rick to stop and help. I wound down my window a little, belatedly thinking of the virus, transmission, ventilation. “I’d forgotten,” I said. “We’re still meant to be social distancing, right?”

“Ah-ha,” the man said. It was less a laugh than as if I’d unwittingly revealed something oppositional, an idiocy. And then, in a tone that was languorous yet stern, “I can assure you. I have a completely clean bell of health.”

I was listening to several things. There was the way his answer fell into separate parts around the pause, like kindling cleaved by a hatchet. There was the way he got the saying a little crooked. Sometimes, when that happens, it has an accidental poetry. Tonight, I wondered what he saw when he said the phrase; what he felt it referred to. The bell you hit with a “test-your-strength” hammer at a carnival? The one that chimes at the top of the pharmacy door as you leave, on a day you’ve been buying lip balm, or nail-clippers, no need for prescription medicines? But I also wondered about his tone. There was something in it of surly scepticism: of don’t come at me with your bullshit.

The reek of drink was still there, even with my window cracked open. Usually on the motorway, my husband asks me to wind the window up after a few minutes, despite the fact the car’s air conditioning is broken. He routinely reminds me about drag and lower fuel efficiency. But a second or two later, Rick lowered his own window too. It was one of those rare situations where it seemed our thoughts exchanged as clearly as folded notes passed from seat to seat.

We’d probably just saved the guy’s skin. If a cop had found him out there, he’d have been breathalysed, and done for drink driving. The fact he had run out of fuel might have actually prevented carnage on the road. Yet his slightly abrasive, fume-soaked air of devil- may-care heightened the fact we could now be endangering ourselves, cooped up with his breathing: virus particles released with each exhale. (Those particles which, under the electron microscope, look like sinister, spiked medieval flails.)

We travelled on in an unaccustomed, electric silence. Our boys usually talk constantly to each other, a mixture of jokes, hoots, brays, fights, admonishments and stories about the “sussy” things other kids have said or done, at school or online, but they leaned against each other, not scrapping about it, just whispering, with their jackets rustling as they adjusted posture in the squash now and then. I glanced around at them once, but they were both gazing abstractedly out the window. I turned back, ignoring the occasional shifting and muffled crackling, trying to let the cat’s-eye road markers become as hypnotic as they were in my own childhood; each one gleaming orange, then whipping past like campfire sparks caught by the wind.

Rick slid a Marlon Williams CD into the car’s ancient stereo. The swift canter and cry of “Miss Lonesome”, the sound of the engine, and our wheels on the road became a distraction. We were getting somewhere, they said: the weird tension in the atmosphere would soon be gone. When we finally pulled up into the gas station the guy said, “Cheers, mate. I’d offer you cash but I’ve got none spare on me.”

“No worries,” Rick said. He looked up into the rear-view mirror to see whether anyone was arriving behind us, wanting the pump we blocked.

“It’s a pay-it-forward kind of thing,” I said, turning around again to watch as the guy undid his seat belt.

“Youse are good people,” he said, but again his tone was ironed of feeling, dull and automatic, as he clambered out of the back. Once he was standing on the station forecourt, he ducked down a little to look into the car. I started on my good luck smile, about to say goodbye, when we met eyes. His gaze was filled with a direct, undisguised dislike. Something cold slid past my ribs and finned into my stomach. One of my hands clenched my seat belt, the involuntary animal part of me readying for something: fight goes to your arms, flight goes to your legs, where did I read that, about the direction of adrenaline surge in the body?

The man drew out a yellow, plastic-handled box-cutter knife from his jeans pocket. The forecourt lights slid and trembled on the angled metal tip. With an oil-stained thumb he moved the blade silently into the safety position, then pushed it into view again: a talon sheathed, unsheathed; a snake’s tongue flickering in and out of its mouth.

When I looked up from his fist, his stare locked again with mine. He returned the knife to his pocket, then took out his mobile, dialling beside the petrol station’s no cellphones sign. “Yo,” he said, into the speaker, then slammed the door.

“Jesus. That’s shut,” said Rick, eyes at the wing mirror, as he released the handbrake and gunned the car.

“Freaky vibe,” said Jake, unfolding his long limbs into the freed-up space.

“Did you see …” I faltered. I wasn’t sure what to say about the Stanley knife. It was a nothing moment, from one perspective. Would he have even been capable of serious harm, in a car with four people trying to stop him? Why would he think of doing anything violent, when we’d plucked him out of a shitty situation?

I wanted to believe the best of people. But the thing is, I hadn’t needed to see the knife to know what was in his eyes. When I thought of the loathing there, and how to convey the chill and the certainty of it, I had to haul myself back from that unpeeling disintegration, the dark-grained abyss that I first felt opening when I was nine or ten, and I learned what some men could do to women.

“I could smell a lot of beers,” Ewan said, then added lightly, “but he gave me this that he made.” He leaned forward into the gap between our front seats, his small, pale hand shaking something back and forth.

I had to ask him to stop and hold it steady for me to see what it was. It had the silhouette of a dragon. Details like the fiery breath, the claws, the spines on its back and tail, and wings a little like the long, graceful fins on a koi, were all sliced away, sculpted like a stencil, into one of Ewan’s sheets of origami paper.

“Oh,” I said. I swivelled around quickly, craning to look back over my shoulder, but the petrol station was already well behind us. I felt an unlatching, as if I’d let something small yet vital slip from a hasp. “Did you say thank you?”

Ewan slumped back down into his seat, and draped the stencil over his face, treating it like an eye-mask for sleeping. A few moments later, he was peering out at street lamps and traffic lights through the lacey paper incisions, with the curious, stilled wonderment of someone using an old-fashioned View-Master for the first time.

When we arrived home, and piled out of the car, there was a snowfall of tiny red and white scraps littered all over the rear seat. For a moment, it looked as if something had disintegrated back there. But as I brushed them into one hand, those papery shards make me think more of a kaleidoscope. Or really, of how a mind could be like one. A person turns this way, or that, and in an instant comes the rapid tumble of memories, feelings, assumptions, unwitting prejudices: radiant or lacerating. All the vivid, angular pieces seem to seize, then just as suddenly keel and jostle: dread, fear, misreading, trust, delight, hope, shame.