Landfall Review - Marilynn Webb: Folded in the hills (Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 2023)

By Landfall - Helen Watson White | Posted: Friday Oct 11, 2024

A Space to Operate If You Were a Woman Artist

A Space to Operate If You Were a Woman Artist (landfallreview.com)

This is a landmark publication in a number of ways. First, it is a rich and enduring record of the touring retrospective exhibition of the work of Marilynn Webb (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kahu, Te Roroa) curated by Lauren Gutsell, Lucy Hammonds and Bridget Reweti (Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāi Te Rangi). Secondly, it is a truly bilingual book, with nearly all the English text translated by the Toi Reo Māori qualified translators Tēnei te Ruru Limited (directed by Komene Cassidy, Ngāpuhi, Ngai Takoto), and the translations placed first. Thirdly, it recognises what the curators call the ‘significant body of research and scholarship’ about Webb that was undertaken during the artist’s lifetime: a solid foundation for the curators to build upon in producing both the exhibition and book. Fourthly, Folded in the hills, as suggested by its title, adapted from a poem by Cilla McQueen, is primarily about relationship to the land, including the damaging ways humans have left their marks, or land-marks, upon it. More positively, Webb herself made other kinds of land-marks—gentle, respectful, sometimes audacious and challenging images of the whenua on paper. That’s what she did for most of her life, and this weighty tome, beautifully designed by the Gallery’s Karina McLeod, tells that unique and memorable tale.

The dimensions of Webb’s lived philosophy and her artistic and activist legacy are outlined in an empathetic introduction by Bridie Lonie. This is supported by a strong biographical backbone in the detailed chronology at the back, tracing the artist’s development in a career spanning many decades. The linear story is fleshed out by photographs and reflections on artmaking in Webb’s own words, quoted from letters and interviews. The art itself is represented in four very full sections of large colour plates—80 in all—which form the substance of the book. Interspersed with the reproduction sections are substantial essays by the three exhibition curators, each providing a different take on the subject and making different emphases.

In the first of these prose pieces, ‘Marilynn Webb: Finding space’, Lauren Gutsell explores the context of selected works from 1968 to 1987 in a story of beginnings. She traces Webb’s journey from student paintings exhibited in 1957 in Stewart’s Coffee House in Ōtepoti Dunedin, through art and teacher training, to her practice as an arts advisor in schools in and north of Tamaki Makaurau, and her travels in Spain, Morocco and Central Australia. Throughout this journey, Webb’s main preoccupation was ‘finding space’ in which to create.

This meant changing her medium from drawing or painting to printing—a significant move in the 1960s, away from what Webb called ‘the built-in hierarchies’ of the world of painting towards the multidisciplinary Bauhaus principles of Auckland’s New Vision Gallery, using the Art and Craft philosophy of her teacher/mentor, Gordon Tovey in the Department of Education. That freedom and opportunity for printmaking, which she called ‘a clean place to operate if you were a woman artist’, allowed her to develop innovative techniques to convey two-dimensional and even three-dimensional lines, spaces and forms on paper.

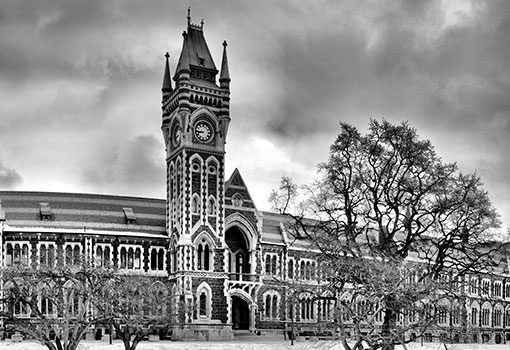

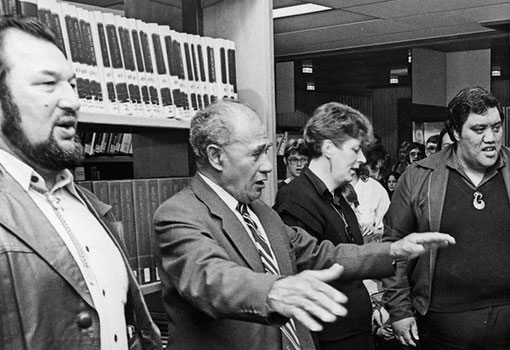

The creation of the Print Council of New Zealand in 1967 ended the era in which printing, like sculpture, was allotted a Cinderella role in relation to painting and drawing. Its well-organised national exhibitions and network of artist colleagues provided Webb with focus and community in what she called a ‘liberated’ space. The authenticity of printmaking as an important art form was established around the same time on the international scene, so after her 1974 Frances Hodgkins Fellowship at Otago University, Webb was able to aim for—if not to achieve—a full-time, self-sustaining career in printing. That said, some of the vivid monotypes called ‘Drawings’ in the first plate section have the appearance of drawings made with a wide paintbrush, showing the printer did not leave her earlier free-form painting practices behind.

On the other hand, her move in the direction of 3D images on paper—through the carving element of engraving and then the embossing of paper with or without ink—established skills that never left her: embossing became one of her most characteristic techniques. A picture from the first section, Cloud Landscape 2 (Linoleum engraving, 1973), was selected for the cover, and it features the only actual embossing in the book—which is immediately appreciated when you hold the book in your hands. Notably, she has embossed the drawing of clouds, not of the land. As she told one interviewer: ‘There’s that unknown but known sky and land vision that I do all the time, and I think that’s Māori. I call it sky talk.’ The effect is often to prioritise sky and clouds over land, perhaps a reaction against conventional landscape paintings that prioritise land. In my perception, the fact that there is a dynamic cloud image over a powerful image of hills simply restores the mythic equality of Rangi (Sky) and Papatuanuku (Earth). And Webb’s interest was always in ‘connection’, the bonds that humans feel, mirroring the relationship between those primeval two.

That is, in an ideal world. Some of the first section’s wild, visceral pictures are labelled ‘Landscape Drawing’ as if to subvert completely what a landscape is, what a drawing is. There is something more at stake. The dualism at the heart of European culture, which privileges mind over body and male over female, has led—as Bridie Lonie intimates—to a yawning gap between humans (male) and nature (female), which Webb wanted to close. Instead, this gap between sky/male and earth/female has become a battleground, the site of many massacres by humans of their own kind—and of lesser species, of whole ecologies.

The first two sections of plates, and both Gutsell’s and Lucy Hammonds’ essays, continue Lonie’s summation of Webb’s passionate concern for ‘landscapes that have been mined, dammed, clear-felled and eroded’—and I would add, burned or irradiated.

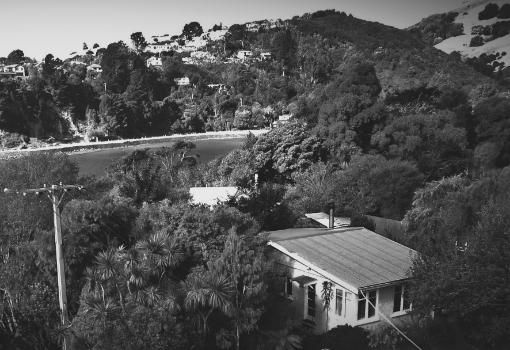

Following on from her acquisition of land near the man-made Lake Mahinerangi and the birth of her son Ben in the 1970s, Webb’s political protest works of the 1980s make up a catalogue of environmental disasters, either actual or foreseen: first, the threat to the delicate ecosystems at the mouth of Otago Harbour posed by pollution from a proposed aluminium smelter (the Aramoana Fossils Series, 1980–81); second, the drowning of the river Clutha/Mata-au in the Cromwell Gorge by a dam at Clyde, which, unlike the smelter, did eventuate (Taste Before Eating Series, 1982, which is reproduced in its entirety, all the pretend-recipes with their satirical charge, in Plate Section 3); and third, the destruction of homelands and habitats by French nuclear testing at Mururoa atoll, exposed in Webb’s Pacific Countdown Series, 1984–86, which Lucy Hammonds describes as ‘enveloping everything from her works at Mahinerangi to Protection Works (1984–93)’. The political significance of Pacific Countdown was amplified, adds Hammonds, by the French-sanctioned bombing of the Greenpeace vessel Rainbow Warrior in the harbour at Tāmaki Makaurau.

After this period of activist art—Webb, in 1986, remarked to Sandra Burt on TV’s Kaleidoscope that ‘art and politics are not divided at all’—Hammonds notes a shift in perception with regards to her social and artistic positioning. Where once Webb had described herself as a ‘loner’, she was now working in association, more aware of her own whakapapa, as she developed projects in the context of contemporary Māori art: ‘Series like Going Through Fiordland (1997–2008) and In Hodge’s Wake (1998) sat in dialogue with works made in response to the Mataura and Waitaki Rivers [Project Aqua]’ and furthered her ‘sense of responsibility towards whānau, hapū, iwi and communities that supported and collaborated with her’. Out of her deepening interest in whakapapa—whether shared or not—and in people’s lived experience of issues like language loss came Webb’s Place Names Suite (2002–09), which Hammonds calls a ‘reassertion of ingoa Māori to the landscapes’.

I note at this point that the meaning of landscape has changed as the book has come nearer to the present day. While it used to mean an object, a painting of a piece of land, and while it still means a horizontal image, when Hammonds uses it, it means the whole land of Aotearoa, especially Te Wai Pounamu. For although Webb grew up elsewhere in Aotearoa, she came to understand the whenua from the point of view of Māori, especially Kai Tahu, who named and lived every southern hill, river and mountain she knew and loved.

It is fitting that the book doesn’t close on the past, with the fact that Webb died before it came to fruition. Instead, it opens up at this point with an essay by rangatahi Māori Bridget Reweti, herself an artist and recent Frances Hodgkins Fellow. Like Webb—and because of Webb—Reweti is moving and acting differently than any wāhine Māori have before in the art world, with the exception of the incomparable Ngahuia Te Awekotuku. She belongs to a collective, working in association, co-editing the first peer-reviewed journal of Māori art, and co-curating a national series of exhibitions made, like this one, into a book. I was grateful that she revisited the opening story of Webb’s participation in the Tovey-led Art and Craft movement alongside now-famous Māori artists like Ralph Hotere, Para Matchitt, Muru Walters and Cliff Whiting. I was even more grateful that she pursued research into what happened to the small minority of wāhine Māori who were Webb’s contemporaries there.

Webb’s feminism has carried over into her teaching and mentoring as well as into her art, and Reweti’s essay shows this while placing strong emphasis also on Webb’s holistic conservation values that are intrinsic to te ao Māori. She writes that Webb’s practice in 1974 was ‘land-based’ rather than working on the traditional ‘landscape’ model, ‘confirming her commitment to what she called “land power” … The prints aren’t documenting what is merely seen but contemplate whenua: the embodiment of one’s connection to the earth, one’s place of birth and one’s return.’ Reweti reveals the depth of connection between tangata and whenua in Webb’s work, which aligns with the work of other leading Māori thinkers like Moana Jackson, who critiqued the Flora and Fauna Claim to the Waitangi Tribunal, finding that the issue there is limited to the concept of intellectual property, whereas the underlying necessity is nothing less than tino rangatiratanga [sovereignty]. Reweti links Webb’s recognition of whenua to Jackson’s and to the basis of that claim, concluding that because the recommendations in the Tribunal’s report are not legally binding, ‘Māori are still sidelined from decisions of vital importance regarding the flora, fauna and wider environment that created Māori culture.’

Whenua, finally, is a much, much larger concept than the land in landscape. All three Māori writers speak with authority on this using Indigenous knowledge, and the final section of plates demonstrates Webb’s understanding of what is at stake in what seems an environmental fight to the finish for all of us. Yet they are also quite sketchy images: a person floating in a swimming hole in a river, with willow branches; an ominous red-toned vision of the Maniototo. Because of the essays, the poems of invited contributors, the symbols with many meanings, and the number of images in a series that comment on each other, this book gives us insight into the possibilities of one artist’s mind stretched beyond the everyday. Folded in the hills is significant in showing Webb’s mahi being commented on by writers who are concerned with how people can not only survive but thrive.

While there is not (yet) a physical monument to Marilynn Webb, this magnificent volume stands as a compendium of her legacy, a broad and deep consideration of the work in art and education that earned her the title of Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit (ONZM) in 2000, and the Supreme Award for excellence and achievement in Nga Toi Māori (Māori Arts) at Te Waka Toi Awards in 2018. And there were many other awards marking her advocacy for conservation: her commitment to the whenua, to the land which she honoured and celebrated, or mourned, in so many different ways.

HELEN WATSON WHITE is a Dunedin writer with a background in university teaching, library work, editing and publishing. She has written many reviews of theatre, books, music, art and opera, as well as articles, short stories and poems. Her photographs have been exhibited in several galleries.