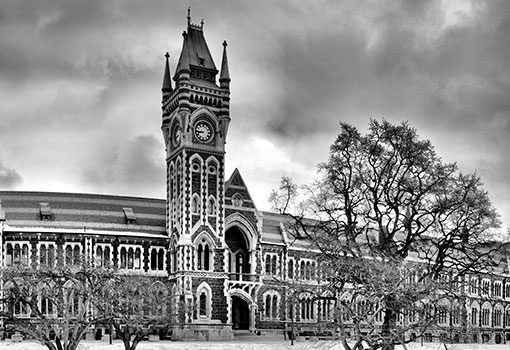

Short story: second place in the Sargeson Prize

By Craig Cliff | Posted: Monday Nov 25, 2024

Our warmest congratulations to Dunedin author Craig Cliff for winning second place in this year’s Sargeson Prize Short Story Competition.

‘Robinson in the Roof Space’ by Dunedin author Craig Cliff has won second place in NZ’s most distinguished short story award, the Sargeson Prize.

Short story: second place in the Sargeson Prize - Newsroom

Robinson is making progress, real progress. Two weeks with this new approach and he’s written more than the past year combined. It’s drastic, for sure: leaving his phone beside the fruit bowl, climbing into the roof space above his garage, kicking the ladder away and only letting Janet resurrect it and permit his exit after at least six hours have elapsed. To call it an attic would be misleading. There is only room enough for him to sit on a desk chair, lowered as far as it will go, slide a tray designed for TV dinners over his legs and bash away at his sturdy, sluggish, pre-WiFi laptop.

It’s not an attic, no sir, but a joke keeps looping in his head.

I cleaned the attic with my wife last weekend. I still can’t get the dust out of her hair.

Janet has never been up here. She played no part in creating the writing nook or concocting the rules of engagement. After some negotiation, she did agree to return the ladder to the edge of the scuttle hole at an appropriate time. “Some of us have to work,” she’d said. “We both work,” he’d replied. “You sell houses, I will sell books. When you pop home, and it’s after three, just slide the ladder back up.” She looked down at her phone. “Your six months are halfway gone,” she’d said and tilted her face back up, its expression halfway gleeful. “You’re a saint, Janny.” “Have I agreed?” “Haven’t you?” “I’ve got to take this,” she’d said and answered her phone, which must have been on vibrate, and must vibrate very gently, because Robinson hadn’t heard anything. He’d listened to her for a bit to be sure there was really someone on the other end of the call, not that he distrusted his wife, but he couldn’t believe a phone could vibrate so near to him and he wouldn’t hear it.

Dust or cobwebs? I still can’t get the cobwebs out of her hair?Either way. Robinson considers how this joke got stuck in his head. How it got in there in the first place. He wants to Google it and see if it can be attributed to one person. Rodney Dangerfield. Tommy Cooper. Don Rickles. Maybe it’s from a Christmas cracker. A joke concocted quickly and without love, a fitting match for a poorly expressed plastic doodad and a festive paper hat that will last about as long as Grandad’s attempts at cordiality. But what if he was the one who’d concocted it, in his sub- or semi-consciousness? What if this joke can be claimed…by him? What if it’s all his? He needs to Google it so bad. What should he do if there’s no trace of this joke online? Tweet it? No, no one tweets anymore. Venture on stage at an open mic night at The Laughter Lab? Work it into his novel? No, not that. Blair and Kimba aren’t at the stage of their marriage where Blair makes housework-related jokes. Dad jokes. Will they ever get there? No, it’s already falling apart before that. Besides, maybe these jokes are what keeps a marriage together – or kept them together in generations past, when gender roles were oppressively clear and people laughed at mild misogyny and, if you think about it, violence. Using your wife as a feather duster. Horrific. God, what would happen if he did tell this joke at The Laughter Lab? Whether its dust or cobwebs, it’ll be pint glasses the intersectionists hurl at him.

No thanks.

He’s making good progress on his novel again. Finally. Hoorah. Praise be.

Two weeks of sequestering himself in the roof space and he’s through the 30,000-word barrier, which might as well have been the sound barrier before adopting this new approach. He’s broken the back of his book, quite possibly. Gotten through all the high school stuff and the hasty marriage and then Kimba not dying and reality setting in and it’s already no bed of roses. Has he got here too fast? Updike spent entire novels in this moment Blair and Kimba find themselves in now. Not that Updike ever had a girl with pancreatic cancer who was given six months to live – as far as Robinson can recall. He’d Google that right now too, if he could, but instead he adds it to today’s list.

Pepsi can 1991

Leukosites [sic?]

Sophie B Hawkins / Sadie Atkins

Cast of Step by Step – where are they now

Jack Black’s real name

Jack White’s ” ”

Updike cancer character

He holds the pen above the jotter pad for a moment, knowing there was something else, then adds: Attic joke provenance.

It’s ten thirty. Today being Tuesday, a quiet day for estate agents who have no tenders closing, he expects Janet to be home close to three. So: four and a half hours to go. If he can manage just 500 words an hour, that’s 2,500 more to the tally. Quality matters, of course. Quality is paramount. But quantity is a prerequisite. You can’t have 50,000 quality words if your manuscript is only 30,000 words long and stalled at the point both Blair and Kimba want out of their marriage but are too chickenshit to do anything about it and there’s another ten years of wanting one thing and doing another before the Inciting Incident that allows both to set fire to this thing they’ve half-heartedly built. Stalled? Careful now. He’s not stalled. He’s steaming along, in the scheme of things. He’s reached a munitions station and is taking stock, replenishing his stores, before another assault. Another 2.5k today! Robinson has a rough idea of the Inciting Incident. He doesn’t want to close off too many options too soon. The answer will come organically from the next ten years of their lives/10,000 words of his manuscript. But, like a psychic groping for phrases to light up a customer’s face, he has some coordinates:

Something to do with a dead dog

Bad weather

Another illness but not cancer

The first use of cancer was deliberate, but doubling down? Nuh-uh. Tread carefully, tenderfoot. There are so many characters that get cancer. In books, on TV, in movies. Blair, in the novel, feels this, seventeen and wrongly pegged as smart thanks to his perfectionist mother who still helps him with all his assignments. The book report on the use of the N-word in Huck Finn. The 1:200 replica of the Gateway Arch, with little figures visible through the 32 windows of observation area, each just eight hundredths of an inch high. When his girlfriend, who wants to be a marine biologist, because don’t we all at some point, is diagnosed with terminal cancer, it’s something for him to do alone. At least, outside of his own family. Thanks but no thanks, Mom. But how to act? Like a character in one of the books or shows where a high school girl gets cancer, of course. He clenches his jaw a little more. Is prone to talking in short, declarative sentences.

I can, I will, I have to.

Kimba, too, knows how beat-up and commonplace it is for some midway popular girl to get cancer in her senior year. It’s not just in books and movies and TV. In group, she learns there’s one of her in every other district. How boring. No wonder she welcomes Blair’s turn as the stoic, set-jawed boyfriend who thinks this is the first time this has ever really happened.

They were only going out a month before the diagnosis. Long enough for Blair to fumble to second base and be turned back on his way to third. They said ‘like’ but were careful not to say ‘love’, even in benign ways.

“I love this song.” Nope.

“I’m loving this spicy mayo.” Nuh-uh.

“Don’t you just love summer?” Verboten!

But what does a stoic, set-jawed boyfriend do when the girl he likes and has felt up gets sick and, after a flurry of tests and tears, is given six months to live, tops? He steps up. How does one step up in this circumstance? Six months gets Kimba through to the end of the school year, through prom and graduation. A TV boyfriend does everything he can to make the last six months of his girlfriend’s life memorable – for her, yeah, but what about the whole school? He can’t bear the thought of his classmates a couple of years later, sophomores in college, struggling to recall Kimba’s name. She needs to be prom queen. She needs to speak at graduation. Burn herself into her classmates’ memories. Her strength. Her grace. Blair sets to work and it’s all so easy. He’s just the sweetest thing. A real trouper. The best. It’s as if he can manipulate high school with his mind. Part the Red Sea of students in the halls between classes. Change the prom theme (goodbye The Eighties, hello Underwater World) and the time the King and Queen are crowned (Kimba can’t stay up past eight). When the moment gets the better of him and he proposes to her in his Prom King acceptance speech, it comes as a surprise to no one, not even Kimba. Okay, maybe his mom. But this only steels his resolve. In a matter of days he’s got everything sorted for the ceremony, which is pencilled in for the weekend before graduation but able to be brought forward if she takes a sudden turn for the worse. He couldn’t make his Gateway Arch stand under its own weight, but look, Mom, a moveable wedding for a hundred guests organised in one week for under three grand! He can replenish his college kick-start fund on the gap year he’ll take to reconsider what he’ll study – event management, maybe? – and to grieve for Kimba, of course.

Robinson knows Kimba needs a bit of work. He’s not sure about her name, for starters. There’s a niggle that an uncle had a dog by that name. The kind of itch that even Google can’t scratch. She can’t have a dog’s name. She’s a person. Three-dimensions. Ups and downs. He can’t remember why he picked ‘Kimba’ anymore. It was from one of his lists, compiled using an online random name generator. He wants to find and replace all the Kimbas in the text, but he doesn’t have a better alternative. Doesn’t have access to the name generator up here.

How does he pee? Janet’s never asked. She probably figures he’s peeing in plastic bottles and doesn’t want to know. She’s right. What other option does he have? On the second day of the new approach, a little stir crazy, he considered peeing through the scuttle hole and onto the garage floor. But no, think of the mess. Think of the dressing down from Janet. She might park her car directly over the puddle, but she’d smell it, surely. So, nope. Nuh-uh. Use the bottles and hold the number twos till after four. What does he do with the bottles? He climbs back up and collects them in the evening, when Janet’s held captive by her cellphone screen, then empties them in the guest bathroom.

Robinson hears something over the whirr of his internetless laptop. Not the garage door opening, but a car door outside. Janet, most likely, popping home to collect some paperwork, or her reusable mug, which she just about never remembers. But there are voices. Janet’s and someone else’s. A client, no doubt. Brought to a quiet, neutral place to contemplate the house they’ve viewed. Maybe Janet is showing them the louvred roof they had installed over the deck last summer. An example of what this buyer could do at the place they’ve just seen. Okay, the other voice belongs to a man. That doesn’t mean anything. The man’s wife might be there too, for all he knows. Could just be soft spoken. Or lost in thought. Or not that interested in the louvred roof and checking her phone. He knows Janet won’t come into the garage to see him. That’s not within the rules of engagement. He looks back at his computer screen, the blinking cursor. Picks up his pen instead, writes:

New name for Kimba

There’s the sound of a champagne cork popping, though it could just be Lindauer – his ears are like his palate when it comes to bubbly: undiscerning. Glasses clink and okay, this is good news. Great news. Janet has made another sale. Another happy vendor. Cheers to that. Team Robinson remains afloat for the foreseeable future. He raises his bottle of water and gives a silent toast to his wife’s successful day. Soon enough it will be him they’re toasting. The day he finishes his manuscript. When he gets an agent. When the book finds a publisher. The day the book comes out. Its glowing reviews in the New Zealand Herald, the New York Times. Maybe he should buy a crate of the French stuff. He’s bound to develop a taste for it by the time he hits the bestseller list. He writes:

Crate of champagne

There is no alcohol at Blair and Kimba’s wedding. For starters he is only seventeen and she is dying of cancer. Also: the cost. Maybe Blair should wonder, at the point the cursor is blinking on Robinson’s word processor, 10 years removed from the ceremony, if it was bad luck to be toasted with tap water and Pepsi Max? But at the time, everyone considers it a success. Just the sweetest thing. It makes the papers. Even his mother takes a clipping before reverting to her antagonistic ways. Blair needs to think about his future. He needs to apply to colleges. He could start in the second semester. In the meantime, he can work at his uncle’s auto parts distributor. You cannot bask in this glow forever. She’s dying, Blair.

Except she doesn’t die. The cancer goes into remission. The oncologist eats humble pie. Soon she can walk to the corner of the street by herself. Her hair grows back, though it never regains its former bounce and volume. She can start swimming again. She learns to drive and still Blair hasn’t started any college applications. His hands smell like degreaser from the end of every shift at his uncle’s warehouse. The smell reminds Kimba of the room she got her chemo in. She doesn’t tell him. He needs to get the grease off. It’d be worse if he came home to the one-bedroom apartment that her folks are paying for while they ‘find their feet’ and left black smudges everywhere. On the refrigerator door, the cutlery drawer, the TV remote, her iPad, which he commandeers every night to play Kingdom Rush. On pillowcases and bedsheets and curtains and photo albums and magazines.

When Kimba’s parents renege on their promise to cover the rent for one whole year – it’s driving them to financial ruin, apparently – and the newlyweds must fend for themselves, Blair’s job and the degreaser are even more necessary, but no less evil.

Then there’s sex. The sword of Damocles hanging over their heads. A sword, at least. Robinson’s not sure exactly what Damocles’ sword was all about. He adds it to his list of things to Google.

Kimba’s cancer has gone into remission long enough that her strength is back and she can swim and drive and think about getting a job to help pay the rent for their tiny apartment but they still haven’t had sex. Haven’t consummated the marriage. For both it feels a great distance to traverse, back to Before Cancer, when Blair made second base and was turned back on his way to third. They are married and have money worries, but they really should be having sex, shouldn’t they?

Robinson pushed them toward the act, but his teenage newlyweds resisted longer than he expected. Without the cancer, they were strangers. Blair couldn’t talk to his mom about it. Kimba’s friends had moved away to college and, besides, they had been fucking boys for years. She didn’t want to be the little virgin in their inboxes. She was the one who was married. The Cancer Survivor. She did ask her doctor, though. Would it be, like, safe to have sex? Maybe, despite the swimming and the shifts she’d picked up at the Stuff’n’Go, she was still too weak? “Oh, you’ll be fine,” her doc said. “Screw his brains out.”

In the end it took a bottle of wine – one glass for Kimba, the remainder for Blair – to loosen them up enough that they could kiss with tongue in front of the television and let their hands explore each other.

There is laughter from the house. They must be on their second stem of bubbly by now. Janet and the vendor. It must’ve been a big sale, which means a big commission. Hoorah! Robinson swigs from his water bottle and admits to himself he needs to pee. Is busting, actually. He stretches an arm out for an empty pee bottle but it’s beyond his reach and he becomes frantic, the pee is coming. How could he let it get to this point? He lunges for the pee bottle and fumbles at his zipper like a tipsy virgin, but he gets everything in place in time for the stream to start. It’s incredibly loud, the sound of his pee striking the bottom of the bottle. Is it always this loud? He worries Janet and the vendor can hear him. How does one explain the sound of one’s husband pissing in a plastic bottle in the roof space above one’s garage? Three words: He’s a writer. Oh, just to hear Janet say those words! It’d be worth a thousand awkward bottle pisses. Speaking of, this one is still going. He tries to read the remaining contents of his bladder and the volume of the bottle, the control he has over his urethra, if that’s the part of him that pinches shut when he needs to stop peeing. He pinches whatever it is and the stream stops with about a centimetre left before the bottle overflows. He gets another bottle, positions it, lets go but only a few droplets dribble out. He’s done.

More laughter. From the timbre of their conversation, it seems they haven’t heard him pissing. Phew. Social cachet: intact.

She has brought men back home before. Twice last week, in fact. But no one has stayed this long. Maybe he’s more than just a residential vendor. Maybe Janet’s branching out, making deals in commercial real estate. She’s got a lot on her plate. Has taken to real estate like a duck to water, or some less tired, more writerly, simile.

Like a squeamish teen to veganism.

Like a dim, impoverished boy to the armed forces.

Like a racist to the comment section of an online news source.

Like anyone to the internet.

Speaking of, that’s why he’s here, isn’t it? To get away from all that and write another 2,500 words. He checks his watch. Revises his estimate down. Where did that hour go? But it’s all writing, really, even the time spent staring off into the distance. Or the time spent staring at the cursor, its impatient blink. Come on, he can hear Blair and Kimba calling from his word processor, we’re miserable.

This is how he knows he’s doing something right. To write is to tango with mental illness. He’s always been an odd egg. He hides it well, but beneath the surface he’s a mess of contradictions, fears, foibles and fetishes. Janet sees him climbing up into the roof space and thinks this is the thin end of the wedge. That maybe he’s losing it, and this writing lark is a symptom of some midlife malaise. But he’s never had it to lose. Or maybe his it isn’t the same as hers. As normal people’s. And writing, when he can defeat the internet and conquer the wide white page, is his way of communing with his it. His weirdness. His superpower: hearing the creations of his own fingertips talking to him. Urging him to move the story on.

Something to do with a dead dog

Bad weather

Another illness but not cancer

Perhaps Blair loses his job at his uncle’s auto parts warehouse? Maybe the uncle dies, or sells the business, or is forced to wind it up because he can’t compete with the multinationals? Whatever the reason, Blair loses his job and they must survive on Kimba’s supermarket shift manager salary. And then the dog dies, the sky opens and one of them catches a cold, only it’s not a cold, and when they finally go to the doctor, a battery of tests reveals…what?

And is it Kimba who is sick again, or is it Blair’s turn?

If it’s Blair, won’t it be delicious if Kimba doesn’t stand by him? If she bails because it’s too hard and they don’t really love each other.

But if it’s Kimba again, Blair can get sucked back into his teen hero vortex. It’s the most he’s felt alive since it turned out Kimba wasn’t dying. But he knows he must fight against the current. It’s a second chance to be selfish. To do the smart thing. Become an event manager.

Either way, someone’s gonna be the bad guy. Unless Robinson makes the sick one deserve it. He or she turns bitter and horrible. Or maybe he or she was already cheating before the diagnosis.

Or maybe they don’t break up on bad terms. Maybe the sickness is what brings them closer. Brings out the honesty at long last. They realise neither of them wants this – the illness, sure, but also the marriage, the living in each other’s pocket – and amicably split, dissolving their relationship at the very point it’s at its healthiest.

And there’s a twinge, as the sick one walks (or is wheeled?) away from the healthy one. They should be happy. Ten to twenty years of wanting to end it, but maybe they’ve been a slave to the past. Maybe if they’d been able to live in the present. To hold tight to the honesty, the openness, the sardonic jokes and silly faces. Maybe that would have been the best outcome. The happiest one. But they’ve ended it. He or she is walking or being wheeled away from his or her husband or wife and has the rest of his or her life to live, free of template, only themselves to blame if it goes wrong.

Yes.

But is it Blair or is it Kimba?

To move the cursor along, he needs to know. It’s now, 30,206 words into his manuscript, that the novel has its fulcrum.

Perhaps he could try it both ways. Just in his head. It’s Blair that gets sick. It’s Kimba. Even if he can do this in his head, doesn’t need to throttle his thoughts back to the speed of his typing, he’ll need a span of time without distraction. No popping corks or muffled real-estate banter. He might have less than an hour until Janet could hoist the ladder. Jesus, the time. Always the time. But is she still home? He hasn’t heard her or the commercial magnate for ages. Were there no sounds or did he just not register them? Surely the front door closing when one or both of them departed, he’d have heard that. So they’re still here? Quiet as church mice. That seems improbable too.

And then, because the alternative is hard fucking work – actually figuring out the turn his novel will take and committing many months to fulfilling this promise – he rips the Band-Aid off and pictures Janet and some rich fuck fucking in the master bedroom, sullying the marital bed, taunting him. The guy’s pants still around his ankles, his fleshy greyish buttocks rising and falling arrhythmically, like a clump of Insul-Fluf being buffeted in the breeze. Janet with her head thrown to one side, as if she’s trying to read the time on the clock radio, as if there’s a pool for how long they can go at it before her flake of a husband jumps down from the scuttle hole, charges up the hall and bursts in on them. It’s the kind of scene that starts a hundred movies. All the detail he was about to deploy to further heighten his rage, the sounds of their lovemaking, the disarray of the bedclothes, there’s no point anymore. He ruined it as soon as he burst in. He was problematic. A selfish middle-aged white-collar man. Even he wants him out of the picture. Enough already. And it’ll happen. Society changes and stories change with it. It’s like the names on the war memorials and service boards in school reception areas. Those last names you never hear anymore – Baskerville, Snodgrass, Thistlethwaite – they were us, and if their descendants are still here, they’re going about their business like the proverbial church mice.

Well, at least he’s made it to two o’clock today before trying to cancel himself again.

Back to the blinking cursor. What is this rhythm based on? Is it the average standing heartrate? The bpm of the Bee Gees’ ‘Stayin’ Alive’? The speed at which a man with a yacht thrusts his throbbing member into your wife?

He writes: Cursor pulse rate.

He pictures his completed manuscript like a Rorschach test. All he needs to do is mirror what he’s already written, take the reader back the way they’ve come, but left is right and up is down, so they arrive at a new but inevitable beginning on the last page. It must be Blair who gets sick. Maybe it’s something in the degreaser? This generation’s lead or asbestos or thalidomide.

What if Kimba finally got pregnant? Maybe this is the moment at the centre of the ink blot, the caterpillar’s body?

Maybe this is why Janet is entertaining men at home during the day. Because they never had a child together and he climbs up into this crawl space every day to think about other people’s lives, to play with them like little dollies. Janet doesn’t have to say anything. If either of them said anything, it would be intolerable.

Instead he tells her about his dolly-fiction, their made-up lives, his daily god-dilemmas – who to strike down with amoebic dysentery or mesothelioma, what to call their dog – and she asks questions from another realm, like: Why is it set in America? Because, because, because he can’t even remember what he said when she asked this question, let alone what was going through his sieve-mind when he chose a US setting. But hold on, there’s a sudden dopamine rush as he realises there’s something he needs to search but doesn’t need the internet for.

He hits CTRL+F and types ‘dog’.

Three results.

…saltiest sea-dog voice

…puppy dog eyes

…like a dog chasing its tail

How can he kill or possibly just maim their dog if they haven’t even got one yet? Wasn’t he supposed to be an engagement gift? A companion for Blair to have long after Kimba expired? This is good, Robinson thinks, there’s at least three places he’d need to insert the dog, and all up that might be another five hundred words. An hours’ work, if he was in the flow.

He Xs out of navigation pane. The cursor returns to the end of the document.

It has been a very long time without downstairs noises. He must have been in a real reverie when Janet and her exclusively business, extremely platonic male associate left. Or maybe he lured her back here under false pretences. Maybe he went along with the louvred roof thing so he could bring her back here, laugh at her jokes and asphyxiate her? Rapidly encircle her head in Glad Wrap and watch as she silently expires, then soundlessly slip out the back door, not even glancing at the louvres as he heads to the fence, scales it and disappears from the face of the earth. Little did he know that Robinson was home and could help the police track him down. His recall of Janet’s movements. The popping of the champagne, though maybe that was the sound of her being bopped on the head with a rolling pin? And wouldn’t he, Robinson, be the prime suspect? It’s always the spouse, isn’t it? What kind of alibi is being up here, surrounded by piss and punctuation? Maybe there’s a timestamp on the document that could prove he’s been up here this whole time.

The cursor blinks back at him, laughing like the Brothers Gibb, ha-ha-ha-ha, because it hasn’t moved. If only he had made Blair extremely sick by now, maybe he’d be able to prove his innocence and the detectives wouldn’t waste their time trying to incriminate him and actually spend it tracking down the murderous son of a bitch. If only there was already a dog and he could just make it run out in front of traffic now, and it would bring Blair and Kimba to their knees. She’d look up at Blair and say, “I’m pregnant.” He’d look at her and say, “I’m dying.”

Robinson lifts the TV dinner tray from his lap, lowers it to the ground and sticks his head over the scuttle hole. The garage door has thin, rectangular windows along the top, not unlike the viewing windows of the Gateway Arch. He can tell the sun is beginning to set, but not if any cars are parked on his driveway. He listens for signs of life from within the house. He is about to lower himself down to the concrete floor below when he remembers his list of things to Google. He crawls back to his writing nook like an injured dog, retrieves his jotter pad, and returns to the opening.

He looks down.

Okay, he thinks, that’s enough work for one day.

The Sargeson Prize was judged by Harriet Allan. Her judging comments on ‘Robinson in the Roof Space’ by Craig Cliff, who receives $1000: “It’s lively and funny as well as fiendishly clever: the writer in the story puzzles away at the options for his characters’ marriage, while downstairs his wife arrives home and drinks champagne with an unknown man. The real story is going on under the writer’s nose, but he can’t get down to find it, even if he were suspicious enough to check it out. And while his novel advances very little and his biggest progress for the day is a list of things to Google, in the process a short story has been written, because of course there are two stories and two writers.”