Poetry Shelf review: Rhian Gallagher’s Far-Flung

Posted: Monday Dec 07, 2020

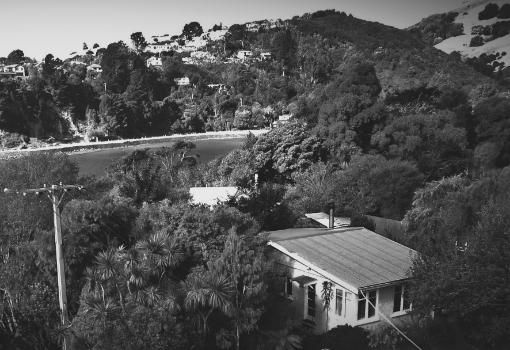

Into the Blue Light

for Kate Vercoe

I’m walking above myself in the blue light

indecently blue above the bay with its walk-on-water skin

here is the Kilmog slumping seaward

and the men in their high-vis vests

pouring tar and metal on gaping wounds

the last repair broke free; the highway

doesn’t want to lie still, none of us

want to be where we are

exactly but somewhere else

the track a tree’s ascent, kaikawaka! hold on

to the growing power, sun igniting little shouts

against my eyeballs

and clouds came from Australia

hunkering over the Tasman with their strange accent

I’m high as a wing tip

where the ache meets the bliss

summit rocks exploding with lichen and moss –

little soft fellas suckered to a groove

bloom and bloom – the track isn’t content

with an end, flax rattling their sabres, tussocks

drying their hair in the stiff south-easterly;

the track wants to go on

forever because it comes to nothing

but the blue light. I’m going out, out

out into the blue light, walking above myself.

Rhian Gallagher, from Far-Flung

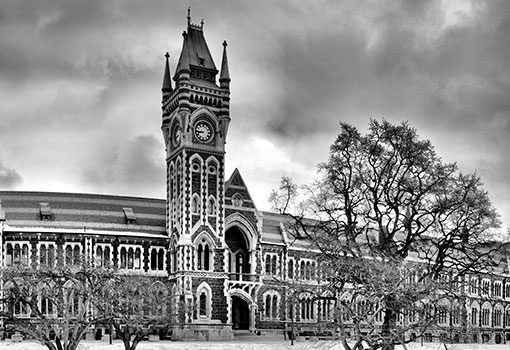

Rhian Gallagher’s debut poetry book, Salt Water Creek (Enitharmon Press) was shortlisted for the Forward Prize First Collection, while her second book Shift was awarded the 2012 New Zealand Post Book Award for Poetry. She has received a Canterbury History Foundation Award, The Janet Frame Literary Trust Award and in 2018 she held the University of Otago Burns Fellowship. This year I welcomed the arrival of Far-Flung (Auckland University Press). It is a glorious book, a book to slowly savour.

Far-Flung is in two sections. The first section, with deep and roving attachments, navigates place. Think of the shimmering land, the peopled land, the lived-upon and recollected land, with relationships, experiences, epiphanies and upheavals. Think of the past and think of the present. Think of school classrooms, macrocarpa and our smallest birds. Think of a nor-west wind and Donegal women. These poems exude a delicious quietness, a stalled pace, because this is poetry of contemplation, musings upon a stretching home along with ideas that have shaped, and are shaping, how the world is.

The other day I turned up in an Auckland café to meet poet Anna Jackson for lunch, and we both brought along Far-Flung to read (if we got to wait for the other). I read the opening lines aloud to Anna when she arrived, and then she started reading the book. We were lost in the book. I am now imagining how perfect it would be to have a weekly poetry meeting with a friend, where you sit and read the exact same book over lunch. Perhaps I am returning to the afternoon-tea poems from my debut book Cookhouse, where I thought I would take afternoon with poets I loved (in the shape of a poem) for the rest of my life. That didn’t exactly happen (in the shape of a poem), but I guess I have been engaging with poetry in Aotearoa ever since.

Rhian’s opening poem ‘Into the Blue Light’ is a form of poetry astonishment. Let’s say awe, wonder, uplift. The spiritual meets the incandescent meets the hot sticky tar of the road repairs, and the ever-moving scene, with its biblical overtones (‘the bay with its walk-on-water skin’), references a fidgety self as it much as it scores physical locations. I keep coming back to the word ‘miracle’, and the way we become immune to the little and large miracles about us. Miracle can be a way of transcending the burdensome body, daily stasis, the anchor of here and there, the shadow of death, and embrace light and engage in light-footed movement. This is definitely a poem to get lost in. You don’t need to know what it is about or the personal implications for both poet and speaker. Perhaps this is what astonishment poems can do: they draw us into the blue light so that we may walk or drift above ourselves.

The second poem, ‘The Speed of God’, underlines the range of a nimble poet whose poetic craft includes the lyrical, the political, the personal and the reflective. Here Rhian wittingly but bitingly muses on the idea that God made the world too fast to get men right.

Or maybe if he’d made man and said, ‘You learn how to

live with yourself and do housework and then I might think

about woman.’

The second section of the book focuses upon voices from Dunedin’s Seacliff Lunatic Asylum and is in debt to research along with imaginings. The Lunatic Act of 1882 defines a lunatic within legal parameters rather a medical diagnosis. The institution was more akin to a prison than a place of healing, with those incarcerated granted no legal rights. As a national inspector of lunatic asylums, hospitals and charitable institutions, Dr Duncan MacGregor ‘feared New Zealand was being overrun by a flood of immigrants from lowly backgrounds’.

Rhian’s ‘The Seacliffe Epistles’ sequence is unbearably haunting. The endnotes acknowledge the sources, many poems in debt to inmate’s letters. Reading the poignant poetry, I am reminded of the way we still haven’t got everything right yet. We still have the dispossessed, the muted, the disenfranchised, the underprivileged. And that is another haunting seeping into the crevices of the book.

Far-Flung showcases multiple bearings of self, place, and across time. There is the child smelling the ‘gum trees in the gully’, rhyming her way across a wheat field, as letters and words start to produce sound and sense. From those tentative beginnings, words now offer sumptuous music for the ear, groundings for the heart, little portholes into our own contemplative meanderings. As Vincent O’Sullivan says on the back of the book: ‘I can think of no more than a handful of poets, whose work I admire to anything like a similar degree.’ This is a glorious arrival, a book of exquisite returns that slowly unfold across months.

https://nzpoetryshelf.com/2020/12/04/poetry-shelf-review-rhian-gallaghers-far-flung/